A year after his wife disappeared without trace in 1991, Richard Klinkhamer, a Dutch crime writer, visited his publisher. He had with him a manuscript which, under the circumstances, seemed a little macabre. Not to mention highly suspicious.

The novel, Woensdag Gehaktdag (a Dutch saying which translates as Wednesday, Mince Day), was a grisly, detailed exploration of seven ways in which Klinkhamer could conceivably have killed his wife, Hannelore. In one of the scenarios set out in the book, he disposes of her body by pushing her flesh through a mincer and feeding it to the pigeons.

When Hannelore Klinkhamer, known as Hanny, went missing from the marital home in the Groningen province in the north-east of the Netherlands nine years ago, her husband was the prime suspect. However, police inquiries were fruitless.

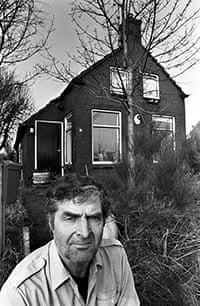

The police questioned Klinkhamer at his home, one of a tiny cluster of houses near the hamlet of Ganzedijk. He denied killing her. They put him in a cell. He denied it again. They searched the house. They searched the garden. Nothing was found. Sniffer dogs searched the garden; the police dug up the garden. A Royal Dutch airforce F-16 flew over the garden with infra-red scanners. Nothing was found.

However strong the authorities' suspicions, there could not be a murder inquiry without a body.

Klinkhamer lived on at the house for several years, writing and drinking heavily. But slowly the suspicion that he had killed his missing wife began to filter out beyond the close-knit community. Details of the manuscript - which his publisher, Willem Donker had rejected as too gruesome - began to surface in the Dutch underground press.

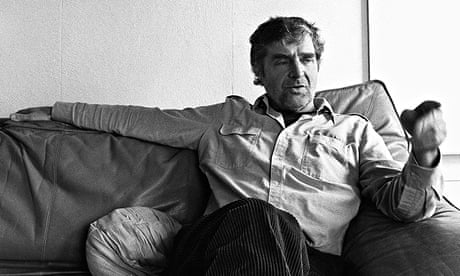

Television programmes started to invite Klinkhamer to make guest appearances. There was an interview with him on Birds of Paradise, a series about eccentrics. In 1997, Klinkhamer moved to Amsterdam, to the Bijlmermeer district, with a new girlfriend. There he surfaced on the literary party circuit, apparently enjoying his new position as a minor cult figure among second-tier crime writers.

Meanwhile, new people moved into the house he had shared with Hanny. In time, they sold up to a couple with children who decided to make alterations to the 200ft garden - getting rid of the tatty shed, for instance.

Then, two weeks ago, they hired a digger. While breaking up the concrete laid on the floor of the shed, the workmen turned up a skull, buried in a piece of clay a few metres below the surface. They went on to uncover a skeleton which a forensic scientist quickly identified from dental records as the remains of Hanny Klinkhamer.

That evening, Richard Klinkhamer, 62, was arrested in Amsterdam. Next day he confessed to his wife's murder and he is now awaiting trial in prison in Leeuwarden, in the north-west of the country.

The present owner of the house seems irritated by the events. "I've had nothing but trouble with this house," she says. The garden has been completely dug up and the spot where Hanny's body was discovered is marked by a thin pole, waving in the wind. A cement mixer whirrs and builders move around the garage and the green two-storey house. Can we come and see the garden? "Only if you are willing to pay 500 to 600 guilders. If you pay the money, you can come in; if you don't, you can leave."

But others who knew Hanny have been paying their respects in various ways. On Wednesday, a small gathering of her colleagues and friends met in Ganzedijk and laid flowers for Hanny, who had been a paediatric nurse at a hospital in Winschoten, half a dozen miles away.

Yesterday, offical tributes appeared in local newspapers. She has been buried, her friends say, somewhere quiet and beautiful. "She was a nice, intelligent woman. Everyone was very fond of her," says Harry Wieters, a near neighbour. It was Harry's wife, Marieke, an old friend of Hanny's from Amsterdam, who first introduced her to Ganzedijk.

According to Dutch newspapers, Hanny's early life was marred, with eerie coincidence, by the murder of her mother. On July 15 1957, when she was just nine, Hanny discovered the dead body of her 46-year-old mother, Maria. She had been thrown downstairs by Hanny's father who then killed her with a hammer. Where he is now, or even if he's still alive, is not clear.

Years passed and eventually Hanny rang her friend Marieke to report that she had met an entertaining, funny man named Richard Klinkhamer in Amsterdam. He was 10 years older and divorced, but she was in love. "She was obsessed by Klinkhamer," says Harry Wieters. Hanny wanted to marry Klinkhamer and bring him to Ganzedijk to start a new life and, in 1978, they moved to the area.

Things seemed to go well at first, but then Klinkhamer, who was a former foreign legionnaire, sometime auditor and part-time author, began to drink heavily. He would hit Hanny and when he did, she would go to stay with other people. "I have seen her with blue marks on her body," says Wieters.

Klinkhamer's writing career, however, began to take off. His first book, Obedient as a Dog, drew heavily on his experiences in the French Foreign Legion. The first thing they teach you, he said, is how to kill somebody; the second, how to dispose of a body properly. He later had a collection of short stories published, entitled Hotel Red.

Like Hanny, Klinkhamer had an Austro-German background. During the war, he once told Willem Donker, that his mother had had an affair with an SS officer. He was in Austria with her when it was liberated by the Russians; he remembers that she was raped. On their return to Holland, his mother's head was shaved - the standard punishment meted out to women who had had liaisons with Nazis during the occupation. "It was a very dark chapter of the liberation," says Donker. "Later, he said, she had to make a living so she did for money what she had done for love during the war."

Klinkhamer, according to Donker, had Nazi sympathies, although other acquaintances reject this. One of his books, Kruis of Munt (Heads or Tails), is a "faction" about the SS. His reasons for killing Hanny will probably never be known but alcohol may have been a factor. In the weeks leading up to her death, as their relationship deteriorated, he was drinking huge quantities of beer on his own at home.

What is known, if Klinkhamer's account can be trusted, is how Hanny was killed. On January 31 1991, when she was 43 - three years younger than her mother when she was murdered - Klinkhamer beat her to death with what the police believe to have been some kind of wooden bat or handle. Then he dug a hole in the shed, dumped her in it and filled it with concrete. He used compost to disguise the smell of the rotting corpse. Six days later, he reported her missing, claiming that he had found her red bicycle at a nearby train station. At last, police launched an investigation.

Friends of Hanny's, including the Wieters, reported the couple's domestic quarrels to police. "I was quite certain that he did it but police couldn't prove it," Harry Wieters says. "It was not very professional what the police did. He was more intelligent than the police."

Donker describes the local police as "incompetent". But Peter Boomsma, spokesman for the regional police force at Groningen, says: "We didn't find anything so we couldn't charge Klinkhamer."

Oddly, there are plenty of neighbours who are still willing to speak well of him, despite his crime. "Richard Klinkhamer was an eccentric man but in our eyes a good man," says Coos Molenaar, who lives opposite. "Many times here he drank with us. He loved his life, he loved to write books. He built in his garden, big monuments. He never talked about his wife."

Had Donker agreed to publish Klinkhamer's blueprint for murder, Wednesday, Mince Day, he might have been discovered more quickly. As it was, Donker, a small but respected publisher who pops up at London trade fairs from time to time, didn't like the book, but suggested that Klinkhamer turn two chapters into a crime novel. This he did and the book that resulted, Ransom, sold around 2,000 copies, reasonable for the Dutch market. In Ransom, a man pretends to have stolen paintings from the Rembrandthuis gallery in Amsterdam, but, in fact, has hidden them in the gallery.

Having read the original book, however, Donker suspected Klinkhamer might have killed his wife and asked him. "It's not yet the time to talk about it," was the cryptic answer. Had the killing remained secret for another nine years, Klinkhamer could not have been prosecuted under the Dutch statute of limitations law. However, during his last years of freedom, he could hardly have done more to attract suspicion to himself, other than erecting signs to his wife's grave. "Everyone is able to murder someone, somewhere, suddenly," he would hint.

John Schoor, a journalist with De Volksrant, a Dutch newspaper, went to visit Klinkhamer's home with his girlfriend and left convinced that he had been passing time with a killer. "He was really working with the fear of people. He made a lot of jokes about dark things, death. It was spooky."

Once, while digging a hole in his garden, Klinkhamer pointed out to neighbours that it was big enough to accommodate a body. "He loved the notoriety," says Donker. "But at the same time, he told me his wife was the greatest love of his life."

In Holland, the gruesomely delicious irony of a crime writer killing his wife and then writing about it has led to public speculation that he killed her to write the book. But neighbours, his publisher and even friends of Hanny will have none of it.

"That's what people say, I am convinced not," says Donker. "I think the murder was an accident and then he got nervous and thought, my God, how can I get rid of the body? And then he put it under the shed."

As is the way of these things, Donker has now revised his opinion about Wednesday, Meat Day, and has already asked Richard Klinkhamer, through his solicitor, whether he would now like it to be published. But now, with a life sentence looming, Klinkhamer has declined.