Claim: The four kings in a deck of playing cards represent Charlemagne, David, Caesar, and Alexander.

Origins: The origins of European playing cards are highly speculative, with Chinese, Indian, and Persian parentage all claimed of them. Despite our lack of knowledge concerning exactly how playing cards came to Europe, we can determine when they arrived with a fair degree of certainty. Although the Italian scholar Francesco Petrarch

century.

The composition and design of playing card decks varied with time and locale (particularly the number of cards in a deck), but the inclusion of both numbered cards and court cards (or "royals") — and the division of cards into different suits — were standard features from early on. Italian decks contained fifty-six cards, included four types of court cards (king, queen, knight, and knave) and were divided into four suits (cups, swords, coins, and batons). As the popularity of card games spread throughout Europe and the demand for decks of playing cards increased tremendously, they ceased to be expensive, hand-painted luxuries and became cheaper, mass-produced commodities manufactured by master card makers via the use of stencils. Around the same time, knaves were dropped from the subset of court cards to bring the composition of a standard deck down to fifty-two cards.

As the Spanish adopted playing cards, they replaced queens with mounted knights (caballeros). The Germans similarly excluded queens from their decks, naming their royals könig (king), obermann ("upper man") and untermann ("lower man"). German card masters also modified the suits, replacing the earlier French/Italian symbols with bells, hearts, leaves, and acorns. The French made further changes, dropping the obermann and re-including the queen; and adopting the German hearts and leaves (the latter turned upright to become the more familiar spade symbol), adapting the club from the acorn, and replacing bells with diamonds (from carreau, a wax-painted paving stone used in churches).

Over the years, various scholars have put forth the notion that the four suits in a deck of playing cards were intended to represent the four classes of medieval society. The Italian cups (or chalices) stand for the Church, the swords the military, the coins the merchants, and the batons (or clubs) the peasantry. Similarly, the German bells (specifically hawk bells) symbolize the nobility (because of their love of falconry), hearts the Church, leaves the middle class, and acorns the peasantry. On French cards, the spades represent the aristocracy (as spearheads, the weapons of knights), hearts once again stand for the Church, diamonds are a sign of the wealthy (from the paving stones used in the chancels of churches, where the

|

|

|

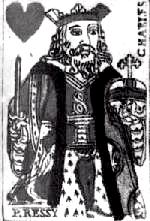

The French suit symbols were more easily stenciled than their earlier counterparts, and the French card masters soon realized they did not need to engrave each of the twelve court cards separately, as their German competitors did. The French simply created one wood block or copper plate for each of the three royals, printed the cards from them, and stenciled the suits in later. The French were thus able to outproduce German card makers, and so the French design eventually became the standard for most of Europe. It was at about this time that the French card masters also started the practice of assigning identities to the royals pictured on their court cards . All of the court cards (not just the kings) were named, and the identities assigned to them (and printed on the cards) were by no means consistent. The choice of names differed from master to master, often with no apparent reason behind them other than personal preference or whim.

Early choices for the identities of the kings included Solomon, Augustus, Clovis, and Constantine, but during the latter part of the reign of

|

The French practice of printing names on court cards came to an end with the French revolution in the late

In summary, the court cards in decks of playing cards were not initially identified by name. The assignation of identities to the kings (as well as the queens and knaves) was a temporary practice unique to French card masters that began around the

Last updated: 29 September 2007

Sources:

Sources:Tilley, Roger. A History of Playing Cards. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1973. ISBN 0-517-50381-6.