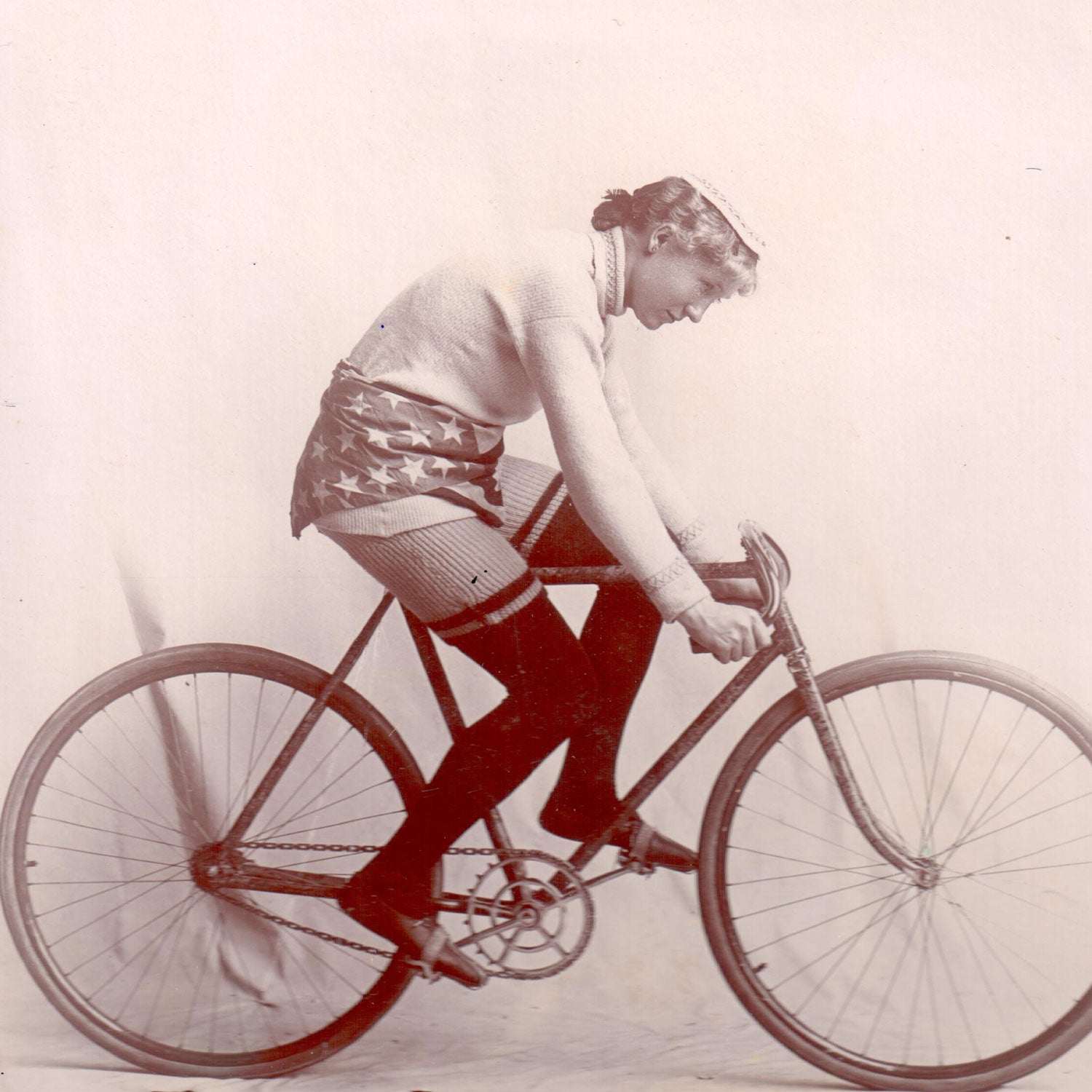

Soon after she arrived in Chicago, in 1889, Swedish immigrant Tillie Anderson decided she needed a bicycle. While scraping together a living as a seamstress in a tailor’s shop, she spotted women sailing by on the new contraptions, looking very free, and she wanted to try it, too. Among her siblings, Anderson was known for her steely will; after two years of saving, she bought her first ride. Cruising through the streets of Chicago, however, Anderson quickly realized that she wasn’t satisfied with pedaling slow graceful loops like other Victorian ladies. She wanted to go fast.

In October 1895, Anderson entered her first race: a 100-mile test of endurance on Illinois roads between Elgin and Aurora. While bicycle riding was fashionable for women at the time, competitive racing was still a novelty—though a fast-growing one. In driving rain, Anderson outpaced the previous women’s course record by 18 minutes. Several months later, in January 1896, she entered her first six-day race, in Chicago. Athletes competed for several hours each night on steep-banked wooden velodromes to see who could ride the farthest. By the last day, Anderson had left nearly everyone behind and was trailing only top pro Dottie Farnsworth. In the last four laps, the crowd thundered and shook the walls as Anderson pushed past Farnsworth and sprinted to victory.

“When the last gong sounded and the race was won the crowd went into a delirium of excitement,” a reporter from the Chicago Tribune wrote the next day. “Men bellowed hoarsely and women screamed. Garments were waved frantically and hats were juggled on canes and thrown into the air.” Because Anderson beat the country’s leading racers, the reporter dubbed her the speediest woman rider in America. Anderson clinched a new record for a six-hour distance, 114 miles, but perhaps more important, she found a new career and her life’s calling.

In the 1890s and very early 20th century, women’s cycling became one of the country’s great sporting spectacles, drawing crowds of as many as 10,000 in cities across the country—often more than college football games or even professional baseball at the time. Women raced the ungainly high-wheel penny-farthings throughout the 1880s, but the advent of the safety bicycle, with its equal-sized wheels, chain drive, improved braking, and lower cost, made the sport more accessible. Women took to the road by the thousands, experiencing newfound mobility and freedom, to the extent that women’s rights activists hailed the invention as a great emancipator. “I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood,” Susan B. Anthony said in 1896.

At the time, male cyclists raced in their own harrowing versions of six-day races. Starting on Mondays, they’d race around the clock as spectators filtered in and out, cheering and heckling. They’d stop only to dust themselves off from a bloody pile-up, down drugs (widely accepted, if not encouraged), or nap on the infield. By the time the racers finished, they were a pathetic lot, staggering off their bicycles and devolving into hallucinations.

Anderson even submitted herself to an examination by physicians interested in studying the effects of exercise on a woman’s body. Newspapers across the country published the results and an illustration of her bare chiseled leg. Her mother was horrified.

According to Roger Gilles, author of the forthcoming Women on the Move: The Forgotten Era of Women’s Bicycle Racing, women’s participation in cycling races led to innovations in the sport that made it a lot more fun—and less gruesome—to watch. Because women were thought to be the weaker sex, organizers set them up to race for only two or three hours a day for six days, turning the event into fast-paced, highly entertaining chaos.

The women competed on small, temporary wooden tracks built inside armories and theaters, with banks as steep as 35 degrees. They sped along at 22 or 23 miles per hour and sprinted around 30 mph—faster than many spectators had ever seen a human being move—elbowing each other, zigzagging around, and sometimes winning by only the length of a bike. Brass bands clanged loudly and paced their tempo with the riders’ speed. Race promoters shouted through megaphones, and rowdy crowds tossed their hats and screamed, tearing down pennants and hoisting up bicycles at the end of the race. In comparison to the men’s races, it was quite civilized.

“The men’s races were more working-class, cigar-chomping affairs, whereas women’s races would attract the mayor, society people, women, and families,” Gilles says. (Although there was still plenty of betting.) “I think it helped a lot to develop what arena sports could be in America…These women need a place in history.”

Among the professional women racers of the 1890s, Anderson was undoubtedly the best. Over the course of her seven-year career, she entered 120 races and won all but 11. Newspapers and promoters played up rivalries between the racers, such as Farnsworth and Lizzie Glaw, but Anderson’s mix of professionalism and fitness helped her to dominate. Although she was sometimes ridiculed for it, Anderson was among the first to train systematically by taking regular training rides, lifting weights, and watching her diet to maximize performance. She was competitive and stoic, leaping up valiantly after crashes, and sported a Muhammad Ali–like swagger about her strength and abilities—couched, naturally, in prim Victorian parlance.

“Three years ago I was very fat in the legs, almost as much so as Miss Peterson, one of my competitors in the St. Louis race, is today,” Anderson told the St. Louis Republic in 1897. “My muscles were not at all developed, though it was but a short time when the fat began to peel off and give way to sinewy strength.”

Anderson also had the advantage of a trainer, fellow bike racer and future husband Phillip Shoburg, who recognized her talent and quit his own career to support hers. Shoburg helped her schedule races, secure lucrative sponsorships, tune her bike, and pace her on training rides. Between her prize money and sponsorships, Anderson was making between $5,000 and $6,000 a year, the equivalent of $140,000 to $160,000 in today’s dollars. But not everyone thought this line of work was becoming of a woman.

“The popular reception was unambiguous—they loved it,” Gilles says. “Thousands and thousands of people went to these races and they had no problems whatsoever. But just like today, the pundits—or the vocal minority—were holding on to these mores and values of a Victorian era and trying to steer people against it.” Some of Anderson’s own friends wouldn’t speak to her after seeing some of the scandalous outfits the women racers wore—long tights, clingy shorts, and curve-skimming sweaters. “Oh, they really thought I was wicked,” she once said.

Anderson herself was unselfconscious. She was proud of being a serious athlete and unapologetic about her muscular physique. Anderson even submitted herself to an examination by physicians interested in studying the effects of exercise on a woman’s body. Newspapers across the country published the results and an illustration of her bare chiseled leg. Her mother was horrified.

“Although Miss Anderson’s limbs are not as regular from the artistic viewpoint…her general health is better,” proclaimed one article in the St. Louis Republic in 1897. “From a comparative feebleness she has grown into robust strength. From head to foot she is a mass of muscles.”

Throughout the heyday of women’s six-day racing, the League of American Wheelmen discouraged women from racing and men from supporting them. Some publications in recent years have reported that the league actually banned women from racing in 1902, but there are no records to confirm that. The sport likely declined for a host of reasons. The advent of automobiles and motorcycles ended the great bicycle boom of the 1890s, shuttering bicycle manufacturers and drying up sponsorship dollars. In 1902, two of Anderson’s best competitors died—Lizzie Glaw of typhoid and Dottie Farnsworth of a cycling accident sustained in a circus performance. Societal discomfort with female athleticism may have also played a role. By 1902, there were no longer any women’s races.

Tillie Anderson pedaled her last race that year, soon after her husband died of tuberculosis. Although suitors courted her, she never married again. She became a Swedish masseuse for wealthy families in Chicago, helped establish bike paths in Chicago in the 1930s, and spent summers at a lakeside cabin in northern Minnesota. Anderson died in 1965 at age 90.

For decades, Anderson was largely forgotten by the general public, but in 2000, with the help of her grandniece Alice Roepke, she was inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame. In 2011, author Sue Stauffacher took interest in Anderson’s story and wrote a children’s book about her life, Tillie the Terrible Swede: How One Woman, a Sewing Needle, and a Bicycle Changed History. This fall, in addition to Roger Gilles’ book, British author Isabel Best will release a yet-to-be-titled book about Anderson and other legendary women riders.

Anderson’s racing calendars, photos, and notes still reside in her Minnesota cabin, where her racing bike is still on display. Her descendants continue to use the cottage and fondly remember her. “She was always really proud of what she did,” Roepke says. “These races would be on the front page of the smallest little town newspapers. People would talk about it around the kitchen table. It surprises me that it was just lost to time.”

While women raced in sporadic events in the first half of the 20th century, women’s cycling didn’t take off again until the 1970s. According to Gilles, based on her times, Anderson would likely keep up with the professionals of the late 20th and 21st century. “It does not fatigue me in the least to take part in these long-distance races,” Anderson once told a St. Louis newspaper. “I am just as fresh after a two-hour’s run as when I commence.”