The 'Golden' Ratio: The One Number That Describes How Men's World Records Compare With Women's

And six other facts about how the genders compare athletically.

The vagaries of gender have been the most consistently important issue in the 2012 Olympic Games. Even before the torch arrived in London, the International Olympic Committee ruled on the gender of competitors. For the first time ever, no nation marched in the Opening Ceremony with only male athletes. On Saturday, the last male-only Olympic sport disappeared with the introduction of women's boxing. And, as if to top it all off, Ye Shiwen's performance seemed all the more incredible, and all the more remarked-upon, because it was better than Ryan Lochte's.*

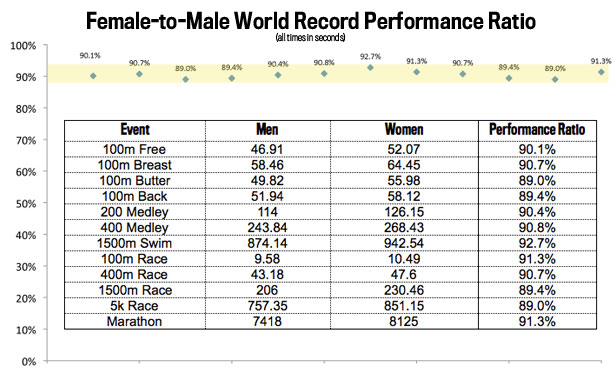

But what are the basics of female performance? How do the best female athletes *typically* compare to men's athletes? In two "basic" feats of human performance -- swimming and running -- here is how men and women compare:

1. Women's performances hover, with incredible similarity, around 90 percent of men's.

Check the graph below: It's a grossly unscientific but accurate comparison of men's and women's current world record times from the "marquee" events in short, middle and long distance running and swimming.

Across the board, women's records stand at about 90 percent of men's. There's some variation there, but not too much: among these races, the women's records all fall within 1.8% of each other.

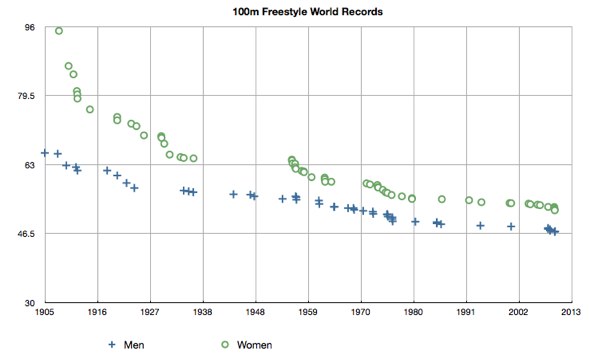

2. The fastest woman swims about as fast as the fastest man did -- during the Johnson administration. In freestyle, the women's world record time is as fast as the men's time was in 1968. In butterfly, the fastest woman swims as fast as the fastest 1967 man (Mark Spitz FWIW). And in backstroke, the magic male-female intersection is, again, 1967.

The only 100m aquatic record that doesn't fall during that period is the breast stroke, where Jessica Hardy meets the 1972 men's record of one minute, 4.9 seconds. (And, in fact, female swimmer Rebecca Soni eclipsed that time before Hardy did.)

3. But women's records have been closer to men's records in the past.

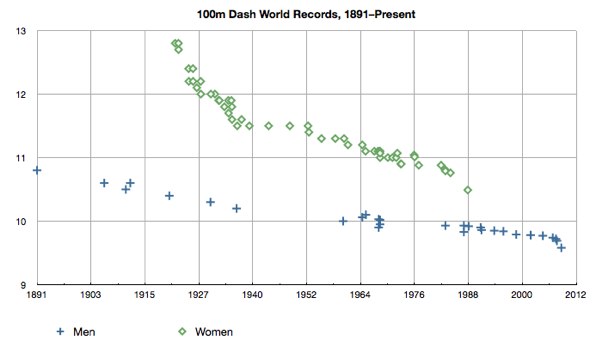

Florence Griffith-Joyner holds the current women's 100m dash world record time, at 10.49 seconds. She set it in 1988. Since then, no one (who hasn't admitted to doping) has challenged it:

In the above graph, look at how close Joyner got to the men's record at the time. In August 1988, when she set her record, she ran at about 95% of where the men's record stood.

4. But Joyner's record -- the fastest female 100m dash in history -- is only as fast as the men's record was in the Harding administration. Despite the fact that Joyner got within 5% of the contemporaneous men's record, she only ties men who ran seventy years before. Her record of 10.49 seconds was surpassed by the American Charlie Paddock, with a time of 10.4 seconds, on April 23, 1921.

5. Over the past century, women's times have improved much more than men's have. Another cool thing about the graph above? See how the women's time quickly shakes out, from what the fastest women with access to the Olympics could run to the time that much more closely aligns with what's possible for the fastest woman. That quick drop -- that's the entire sports training societal complex reorienting itself, becoming more socially egalitarian (and economically successful) by turning its attention not just to talented boys, but to talented girls. The same hastily meandering movement downward is present across contests, like, for example, in this graph of women's 100m freestyle performance.

It stands to reason that, as societal structures improve even further, women's records could continue to improve as well.

6. In swimming, certain strokes seem better suited to women. Decade on decade, women are better able to close the gap with men in the backstroke and freestyle.

7. And generally, very long races seem to benefit women. Looking at the table above, of men's and women's records across a range of different races, women come closest to men's records on races that depend on aerobic strength: the open water swim and the marathon.

Will women's records ever converge with men's? Derive a line from any of these scatterplots, and the computer tells you "yes." At some point this century, the algorithm says, women will catch up to the stagnating male sprinter and swimmer.

But the athletes here are Olympians, world-record holders: all swimming, sprinting and running near the peak of human ability. They are anomalies, and the success of any nation's elite athletic program springs from its ability to support, select and train its anomalies.

So when trying to tell the future from these data and charts, we're not talking about male and female future performance generally, but the performance of the athletically elite. Will anomalous women catch up to anomalous men? Maybe. Maybe they'll converge.

Or maybe they won't. Many nations, after all, already nurture their athletes from cradle-to-Game. The lesson of Griffifth-Joyner's almost 25 year-old record might be that we've reached the end of unaided female performance. In the 100m dash, we've gone as far as even the elite can go.

But what's most likely of all is that their convergence will be far more complicated than we can imagine. We'll never be able to answer how fast the unaided male and female can run, because doing so raises all sorts of questions about the nature of unaided-ness. A super-strong sprinter or swimmer in 2054: Will we ever know for certain they weren't engineered to be that way? At what point does an anomalously strong woman become a normal man -- or an anomalously strong man? For if we derive a line from globalism's scatterplot, and another from the Olympics', and expect both of those to hold: What kind of anomalies will be revealed then, when a historically unprecedented number of developed nations scour a historically unprecedented number of citizens for a historically unprecedented talent? That, it seems, may be the most interesting.

--

*As commenter Bobbie119 notes, I should clarify here: Ye swam a faster final 50m split than Lochte's final 50m split. He finished with the better time; she, with the superior performance.