The ‘greatest film-maker who ever lived’

Criterion

CriterionIt’s not right that the Swedish master Ingmar Bergman is always described as dark and gloomy. He was a deeply humane artist with great empathy, writes Benjamin Ramm.

Woody Allen once lauded Ingmar Bergman as “probably the greatest film artist, all things considered, since the invention of the motion picture camera” – yet he is also the most misunderstood. Ten years after Bergman’s death, the received wisdom about his work continues to obscure his legacy, and discourages new audiences from discovering his achievements.

The obituaries a decade ago were predictably clichéd: Bergman’s films are ‘morbid’ and ‘pitiless’, ‘a long, dark night of the soul'. Yet the primary theme of Bergman’s work – the thread that links all his films together, across genres – is not death but the redemptive possibility of love. His bleakest visions relate not to mortality but to isolation and rejection; in particular, to unrequited love.

At times, the caricatures have been wholly misleading. Bergman’s relentless inquisitiveness is characterised as ‘cerebral’, suggesting an abstract loftiness, when in fact his work is intensely visceral. Bergman is categorised as ‘austere’, despite his playfulness, exemplified by Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), and the sensuality of many of his key works, including Persona (1966) and Cries & Whispers (1972).

Criterion

CriterionSimilarly, Bergman’s eloquence has been mistaken for sophistry, when in reality he mistrusts language and his work perpetually cautions against what he termed “the restrictive control of the intellect”. Those who regard Bergman as ‘elite’ ignore that his films are wary of authority (clerical or political) and his characters find wisdom beyond knowledge, in the comforts of human communion.

In over 60 films in a career spanning six decades, Bergman charted the harrowing cost of what he called “emotional poverty”. His work in all its variety is arrayed against the cynical, clinical, calculating, careless, and callous; he decries our lack of compassion and our “empty but clever” irony. What makes Bergman radical in our own era is his unfashionable sincerity, which leaves him open to mockery and parody.

Criterion

CriterionFor all his earnestness, Bergman had no pretensions about his art; his work is sceptical of its own power, as seen in his 1958 film The Magician, and even more so of the virtue of artists, depicted as parasitical creatures feeding off the turmoil of their subjects. Yet art can provide consolation: Bergman found “human holiness” in the music of Bach, which offers his characters “a flickering light”.

Scenes from a soul

Unrequited love began at an early age for Bergman. “I was an unwanted child in a hellish marriage”, recalls the protagonist in Wild Strawberries (1957), echoing the director’s own feelings. From his first screenplay, Torment (1944), to his last, Saraband (2003), Bergman portrayed adolescent rebellion and often futile attempts at reconciliation. In his autobiography The Magic Lantern, he asks his mother: “Were we given masks instead of faces?” She kept young Ingmar at a distance (“I used to try to find ways to win her love”) and he was prohibited from addressing his parents with the intimate du. In Persona (the title derives from the Latin for ‘mask’), an isolated child reaches out to a fading image of his mother.

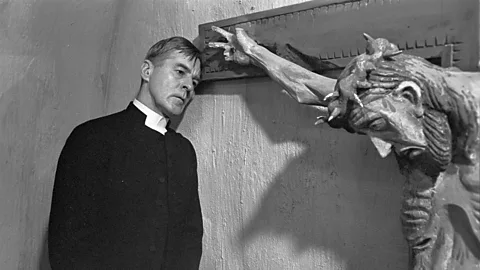

Bergman’s relationship with his disciplinarian father, a Lutheran pastor, was overtly hostile. In his surrealist horror film Hour of the Wolf (1968), an unsleeping anxious artist recounts those physical and psychological punishments that he received as a child. Grown men in Bergman’s films are frequently emotionally stunted, hindered by pride and the fear of humiliation – traits they pass on to their sons. In Winter Light (1963), it is suggested that the greatest torment of Christ was the pain of abandonment by his father: “My God, why have you forsaken me?”

Criterion

CriterionThe absent spiritual father, if he exists at all, is inscrutable: his face is hidden and the devotion of his children is unrequited. Tomas, the doubting pastor in Winter Light, senses not a gentle fatherly figure with “benign answers and reassuring blessings” but “a spider-god, a monster” – the form in which God appears to schizophrenic Karin in Through a Glass Darkly (1961). It is Karin who remarks memorably that we are “like children cast out into the wilderness at night”.

Through a Glass Darkly, like Face to Face (1976), is a reference to Corinthians 13, a paean to love. Yet for Bergman the Church’s model of Christianity is not one of compassion but of obscure superstition, tortured confession and obedience to a vengeful God. Nor are clerics the keepers of their flock, to whom they appear judgmental and lacking in sympathy. In Cries & Whispers, the pastor visits the deathbed of Agnes but offers little consolation to her sisters, instead decrying “this dark and dirty earth, beneath an empty and cruel sky”.

Criterion

CriterionIn this context, it is worth reconsidering Bergman’s most iconic work, The Seventh Seal (1957), which takes its title from the Book of Revelation 8:1, an allusion to the silence of God. The film’s protagonist is a disillusioned knight who has returned from a decade fighting in the Crusades, only to find the personification of Death accompanying him on his final journey. The famous confession scene is cited as an example of the burden of disbelief, but the knight is most troubled by his own alienation: “My heart is empty. The emptiness is a mirror turned toward my own face. My indifference for my fellow men isolates me from them”. When the knight speaks of his “unpleasant companion”, it is not Death but “myself”; he experiences respite only in the company of loving strangers. The knight seeks knowledge, yet even the Grim Reaper cannot help him (“I am unknowing”). Instead, he finds redemption through “one meaningful deed”, an act of selflessness that gives his own life purpose.

Searching for answers

Bergman’s Christian humanism is inspired not by theology, about which it is ambivalent, but by empathy, and values such as mercy, humility, and grace through good deeds. A critic once wrote that “Bergman was interested not in saving souls but in baring them”, but one can sketch a notion of salvation in his depiction of Christian love and its virtues – fidelity, sanctity, devotion.

Conversely, Bergman treats the silence of God as a symptom of a closed heart rather than a closed mind. In Through a Glass Darkly, Karin’s suicidal father has a liberating epiphany: “I don’t know if love is proof of God’s existence, or if love is God himself… Suddenly the emptiness turns into abundance, and despair into life. It’s like a reprieve from a death sentence”.

Criterion

CriterionBergman associates a lack of love with a loss of meaning. When we are loveless, the world appears to us as dull and deformed; when our love is unrequited, it mutates into spite and contempt. For Bergman, love is a form of protective care, a balm that soothes and sustains. Love involves a partial abandonment of the self: the greatest privilege is “to be allowed to live for someone else”, in the words of Tomas’ longsuffering parishioner.

At the heart of Bergman’s humanism is a commitment to intellectual and emotional honesty. Even when his subject is the medieval Crusades, Bergman’s concerns were contemporary to his audience. In the reflections of the anguished knight, it is possible to discern the arguments of Sartre in his 1946 essay Existentialism is a Humanism. Post-war and Cold War anxieties suffuse the films: as a character in Hour of the Wolf asks, “The glass is shattered, but what do the splinters reflect?”

Criterion

CriterionBergman had an abiding fascination with mirrors, fixating on the female human face (“no-one draws so close to it as Bergman does”, noted the New Wave director François Truffaut). Bergman explored how our image of ourselves is refracted through the perception of others, distorting our sense of self. “If anyone loves me as I am, I may dare at last to look at myself”, says Eva in Autumn Sonata (1978).

Perhaps the most significant influence on Bergman’s outlook is the work of Freud – for his excavation of childhood trauma, his analyses of neuroses, and his theories of the unconscious. “It is not my dream, but someone else’s, that I have to participate in”, laments a character in Bergman’s subtle anti-war film Shame (1968). His most personal film, Fanny and Alexander (1982), inhabits the boundaries between fantasy and reality.

Criterion

CriterionDespite his immersion in contemporary philosophy, Bergman was sceptical of the embrace of ‘free love’ – even if his films were among the first to feature a nudist scene (Woody Allen recalls the excitement that greeted Summer with Monika, 1953). For Bergman, sex without love is meaningless: in The Silence (1963), lust and loneliness are inextricably linked.

Bergman was even less trusting of marriage – he was divorced on four occasions. Among his 170 theatrical productions, Bergman frequently directed the work of Strindberg, and he shared his compatriot’s discomfort: Strindberg noted that ‘marriage’ in Swedish means both ‘gift’ and ‘poison’. In the harrowing Scenes from a Marriage (1973), Bergman suggests that the institution stifles and suffocates love. Liv Ullmann, the most brilliant of Bergman’s reparatory cast, attributed their end of their romantic relationship to his need for “the mother” – the unconditional affection he lacked as a child.

For Bergman, the cardinal sins of humanism are “selfishness, coldness, indifference” (Cries and Whispers), each resulting from a deficit of love. But there is nothing facile to his creed: love demands forbearance, forgiveness, and a sacrificing of the ego. Bergman’s bleakest films, such as The Passion of Anna (1969), catalogue the consequences of insufficiently committing to love.

Bergman once remarked that death is “a very, very wise arrangement” – it offers a bookend to our lives, which we can infuse with meaning through love. There is suffering in the world, and we must try to comprehend it, even in its senselessness, but above all we must seek to mitigate it with mercy and generosity. Bergman would like us to remember Agnes’s diary entry: “I have received the best gift anyone could have in this life. The gift has many names: affinity, fellowship, human contact, affection. I believe this is what is called grace”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.