Rare Saltwater Lakes Filled with Jellyfish Found in Indonesia

Armed with new research, a team of scientists has been working with Indonesian governments on conservation management.

Picture yourself diving through a serene body of water in tropical Indonesia. Rays of sunlight penetrate the surface of the water, heating and brightening it up. As you breaststroke through the salty surf, gelatinous, tentacled creatures begin popping up all around you, their pale-yellow bodies contrasting with the bright blue of the water.

Suddenly, you're swimming alongside countless semi-translucent, coffee mug-size golden jellyfish. Unlike some larger, more venomous species, these jellies can't hurt you. Golden jellyfish, like moon jellies, have a sting so minor humans can't feel it.

There are about 200 marine lakes, or small, landlocked bodies of seawater, known to science. Of those lakes, only a handful contain jellyfish, like famous Jellyfish Lake in Eil Malk. Often found in Palau, Vietnam, and Indonesia, the remote locations of these lakes make them difficult for researchers to study. (Read about why Jellyfish Lake is running out of jellyfish.)

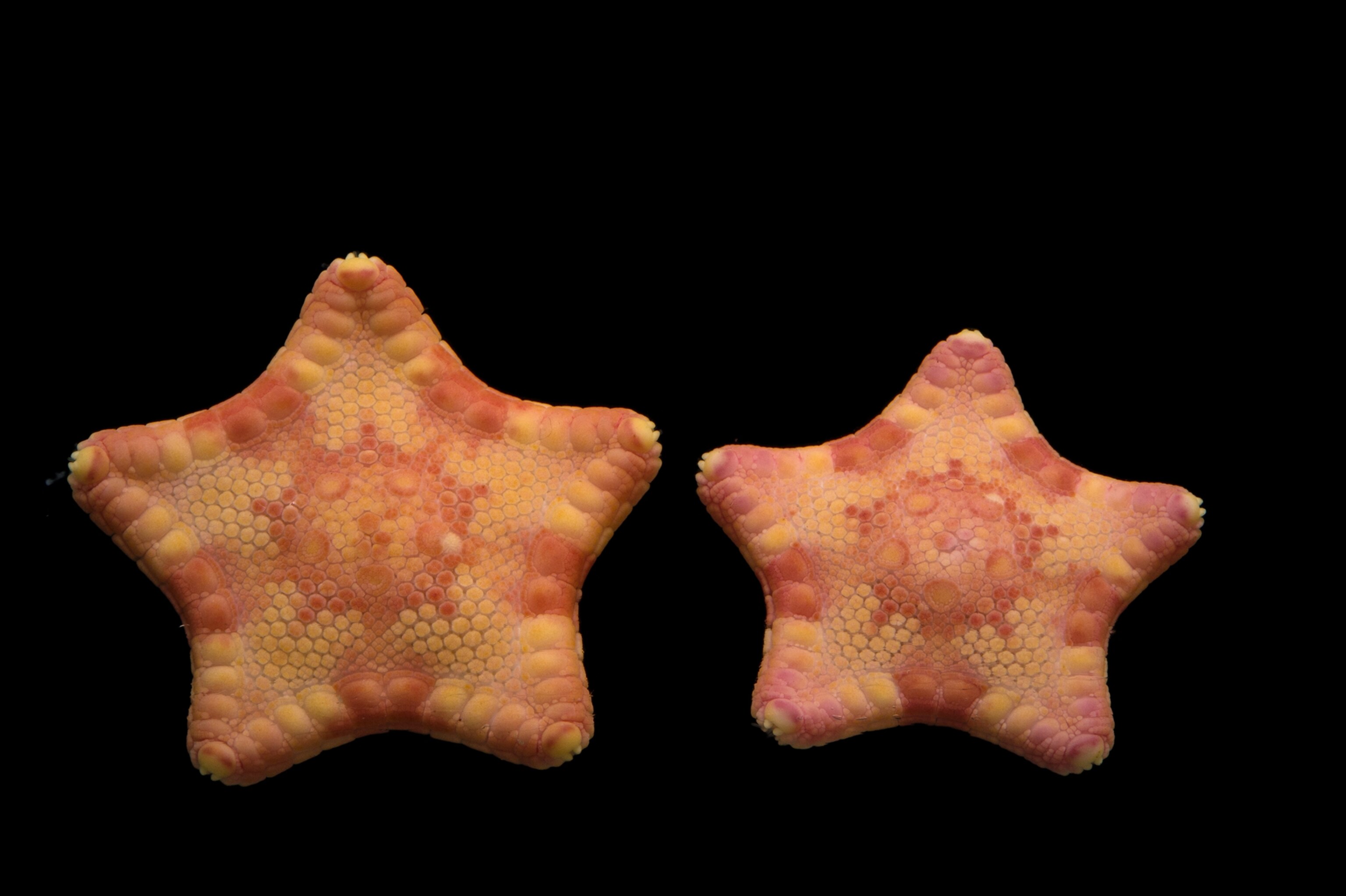

Related: All About Sea Stars

But with the help of the National Geographic Society, marine biologist Lisa Becking did just that. From her base at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands, Becking gathered up a team of like-minded researchers to travel to the Raja Ampat islands in West Papua, Indonesia. On expeditions in 2011 and 2016, they studied the lakes, documenting biodiversity and mapping out ideas for conservation management.

Swimming With Jellies

Marine lakes are formed in karstic landscapes that have been carved out of eroded limestone. The area of the expedition has plentiful karst deposits, making it prime real estate for marine exploration.

Between trekking and gathering samples, Becking and her team filmed two hours of aerial footage of local marine lakes. Then, after combining that footage with Google maps and old Dutch maps, they found 42 marine lakes that had not been documented before.

"They're kind of like island systems," Becking says, referring to how salty marine lakes are isolated from the rest of the sea. "Islands play a crucial role in biology generally because they're an ideal setting for studying how biodiversity is formed. They're kind of like these giant natural experiments."The team visited 13 of these lakes during the expeditions and found that four contained jellyfish.

Protected from winds by surrounding cliffs, the lakes are meromictic, meaning they're composed of layers that don't intermix. They're about 65 feet deep, and they have an anoxic layer about 26 feet down, where the pitch-black water is oxygen-depleted and filled with bacteria. Below that is a layer of hydrogen sulfide, which is dangerous to human divers.

Up at the top, the waters are shimmering with colorful golden jellyfish and moon jellies. Throughout the day, these species make daily migrations to follow the sun, congregating tightly in the sun-filled parts and avoiding the shaded sections. (Related: "Blue Herons, Jellyfish, and Other Animals With Daily Commutes")

"This surface is just bubbling with the [grown] medusa," Becking says. "It's quite a colorful event."

Beyond the jellyfish themselves, more than a hundred species of sponges inhabit the lakes' coasts, colored in shades of purple, pink, blue, and yellow. Becking and her team discovered at least four new species during their expeditions. (Related: "The Surprisingly Complicated Construction Work of Simple Sponges")

Becking swam alongside jellyfish before these expeditions, and she recalls the experiences as frightening and counterintuitive—we are taught from a young age to avoid jellyfish because of their hurtful stings. But with their harmless jellies, these lakes are actually quite the tourist destination because they allow divers to swim alongside the creatures without the threat of being stung. Since that first swim, Becking has bopped with jellyfish many times. (Related: Watch a sea turtle eat a jellyfish like spaghetti.)

"They move on their own and they're just sort of bumping against you all the time," Becking says. She adds that the jellies tend to hover around her water-proof notepads when she's jotting down notes, "very much like a cat, although I don't think they're actually asking for attention like cats do."

The next step for Becking and her team is to go back into satellite images from the 1970s onward. From that data, they'll look at the color of the lakes—an indication of if there are jellyfish or not—and see how those shades change over time and why. They may be able to link this data with changing temperatures.

"There's still a lot more to explore in the sea," Becking says, "and I do think that kind of exploratory work does lead to a better understanding of the ecosystem."

Preserving Blooms

The ecosystems that marine lakes host are fragile. Isolated but still maintaining subterranean connections to the sea, the lakes are particularly susceptible to climate change. Their waters are warmer and saltier than the open ocean, which provides a sneak peek into how oceans might fare if climate change continues at its current rate. (Related: "Climate Change May Shrink the World's Fish")

Jellyfish have lived in the ocean longer than any other macroscopic creature, and climate change could actually be to their advantage, because they tend to thrive in warmer waters. But not all marine lakes have medusas, the bell-shape organisms you probably think of when the word "jellyfish" comes to mind. Some lakes have young polyps that hang out on the lake bottom, or reduced populations all together. Salinity and warm temperatures might also influence jellyfish numbers.

These warm conditions also make for unique species. Of all the species the team sampled, at least a quarter of them seem to be endemic.

When Becking and her team traveled to the area, they had to coordinate their own travel. Now, there's a ferry that goes out to the islands twice each week, making them more accessible to tourists. The lakes are often used as aquaculture ponds, and are plagued by invasive species and litter.

The team has presented its findings to local and regional governments, and now they're working together on conservation management for the area. On a local and regional level, they plan to carry out monitoring efforts next month.

"Ecotourism can be very beneficial," Becking says. "At the same time, if there's no regulation, it could very easily be too much. The problem is we don't know how much is too much."

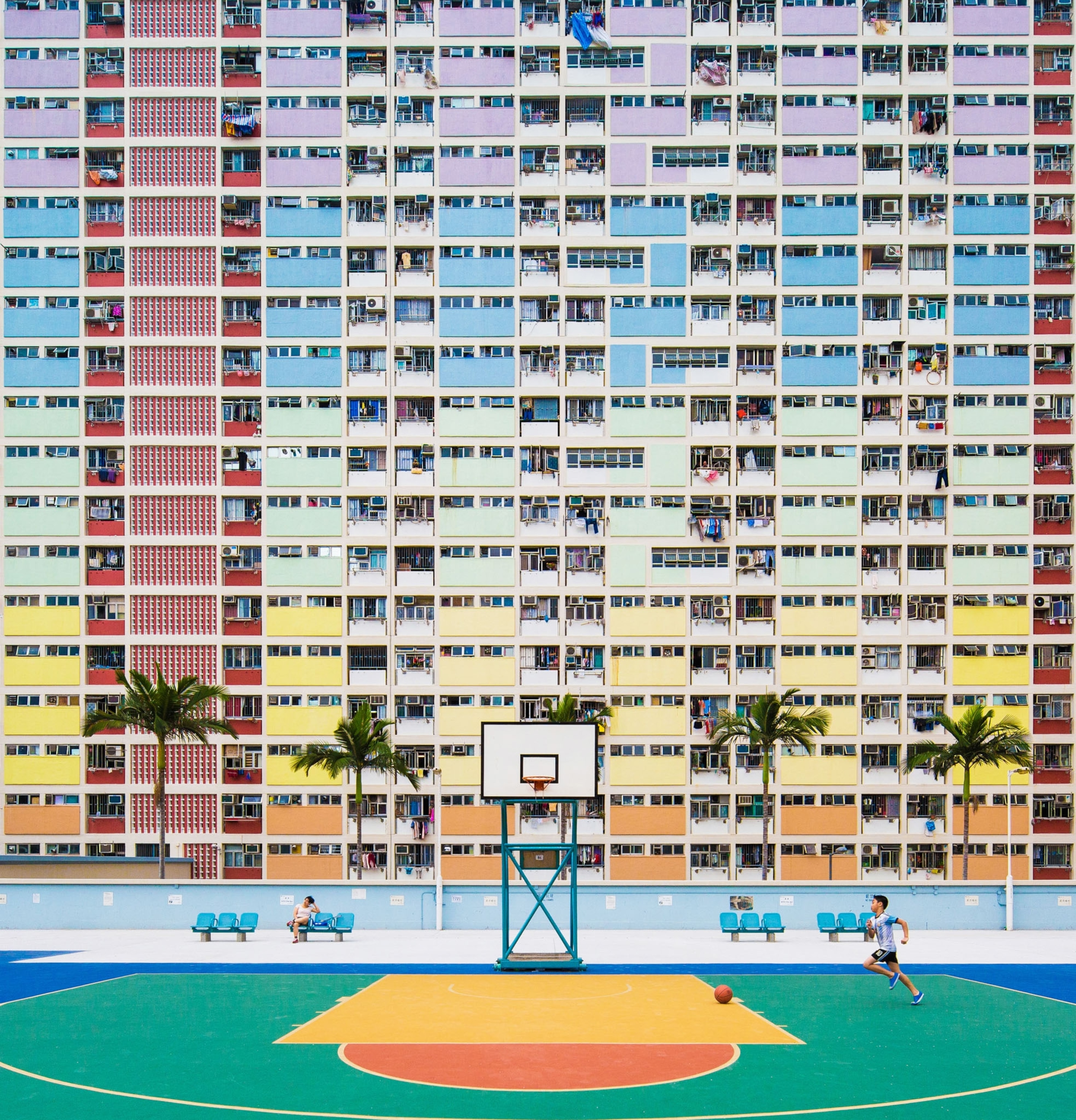

Related: The Most Colorful Places in the World

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- Charlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a diseaseCharlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a disease

- See how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summerSee how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summer

- Why are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagersWhy are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagers

- These pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eatThese pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eat

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

Environment

- 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- Think customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaintThink customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaint

- The tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in AmericaThe tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in America

- The missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold caseThe missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold case

- When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?

- I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

Science

- How being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personalityHow being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personality

- Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?

- Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?

- Epidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save livesEpidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save lives

Travel

- 7 things you need to know about European travel this summer7 things you need to know about European travel this summer

- These Algerian communities live in the Saharan sand seasThese Algerian communities live in the Saharan sand seas

- This German city doesn’t exist, according to a conspiracy theoryThis German city doesn’t exist, according to a conspiracy theory

- The best way to experience Slovenian cuisine? On two wheelsThe best way to experience Slovenian cuisine? On two wheels