1,458 Bacteria Species 'New to Science' Found in Our Belly Buttons

But most bacteria are, like people, "either good or simply present."

Instead of taking your fingerprint, maybe police should swab our belly buttons with Q-tips. No, that's ridiculous, actually. But the idea illustrates a point made by a group of North Carolina-based researchers in their new Belly Button Biodiversity (BBB) project. Last month, the group published results of their first of many experiments, in which they swabbed 60 belly buttons and identified a total of 2,368 species of bacteria. People's individual profiles were snowflake-ily, bacterially unique.

As the BBB understands it, like exploring the depths of our majestic oceans, there's much to be learned from our belly button hangers-on. National Geographic reported that 1,458 of the species "may be new to science," and some of the bacteria were entirely out of their known context. One person's belly button "harbored a bacterium that had previously been found only in soil from Japan," where he had never been. Another had two types of "extremophile bacteria that typically thrive in ice caps and thermal vents."

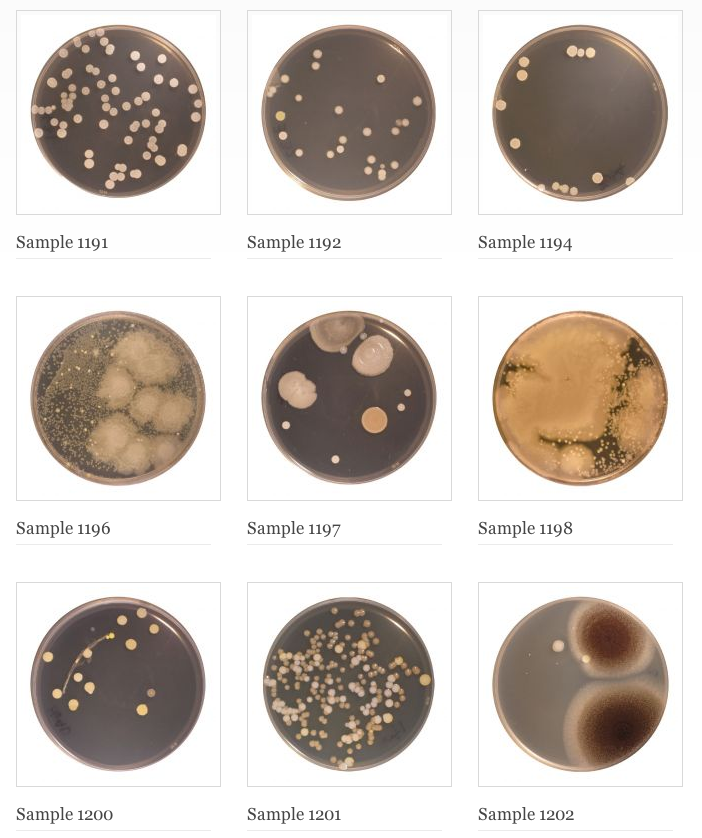

Anonymous samples from a belly button sampling event. Which one are you? F/M/K?

Anonymous samples from a belly button sampling event. Which one are you? F/M/K?"The belly button has captured the imagination for centuries," BBB notes on their impeccably-URL-ed site, WildLifeOfYourBody.org. Prior to those centuries, belly buttons captured no one's imagination. To be fair, in those days, imaginations were much less amenable to capture. They wandered, wily and free, with a discerning taste, the likes of which our indolent, Internet-weary imaginations of today know nothing.

When you return from this journey into the belly button of your mind, you can participate in one of the BBB's very real "sampling events," where you volunteer to be navally swabbed with a Q-tip. They then assign you an anonymous number, and in a few days you can then go online and look photos of what grows -- your belly button bacterial profile -- and learn about the little beings with whom you share your body.

If you're just starting to date someone, or more seriously vetting them as a marriage candidate, you might suggest going to one of these sampling sessions as a fun date. But then, like so many dates, it's actually a test to see how dirty they are. It's anonymous, yes, but if you stand next to each other in line, you'll know what their number is, and you can look it up later.

It's up to you how you interpret the results. Dirtier is not necessarily worse, and that's one important point BBB wants their work to make. The vast majority of bacteria in the world live in harmony with us, and don't want to kill us. No, they want us to live and thrive, so we can keep being their warm homes. So they may actually be helping us.

As the BBB puts it, most bacteria are, like people, "either good or simply present."

So should you be making extra effort to clean out the many bacteria in your belly button? I say no. Unless it's visibly grimy, or you have a history of belly button infections, or just reading about this research no longer allows you to live comfortably with the knowledge that you are an infestation. Others will disagree -- like Dr. Claire Cronin of the Massachusetts Medical Society. She notes that in the era of laparoscopic surgery, where the belly button is commonly used as a port of surgical access, there is virtue in keeping tidy down there:

There is a surprising lack of awareness on the public's part as to what can accumulate in a belly button ... the volume of material increases as the patient ages and, just like their arteries, can harden. I like to think of it as a cache of a lifetime of little treasures. ... Most patients have not received adequate instruction on proper umbilical hygiene. It has not received the same level of attention that the area behind the ears has. ... There is a technique to cleaning the belly button. It involves soap and water and gentle probing. ... Alcohol should not be used, in order to not disturb the delicate pH balance of the area.

Beyond worrying about the embarrassment of doctors discovering "blackened wax casts," in your belly button, though, the BBB project could make important progress in understanding how the bacteria that colonize us actually affect our health. Analogous to the parasite Toxoplasmosis gondii -- which we only recently found out is present in 20-50 percent of our brains, subtly shaping our personalities and maybe even making us try to hurt ourselves -- some of these little bacteria that go unnoticed are probably affecting us in ways unknown, good and bad. Ways that we're currently just chalking up to chance or genetics or God or gluten.

Meanwhile, BBB is now in the pilot phase of testing armpits, which is less fascinating, but doesn't lose sight of their thesis that "in all likelihood your body hosts species that no scientist has ever studied." That's not meant to be used as a pick-up line.