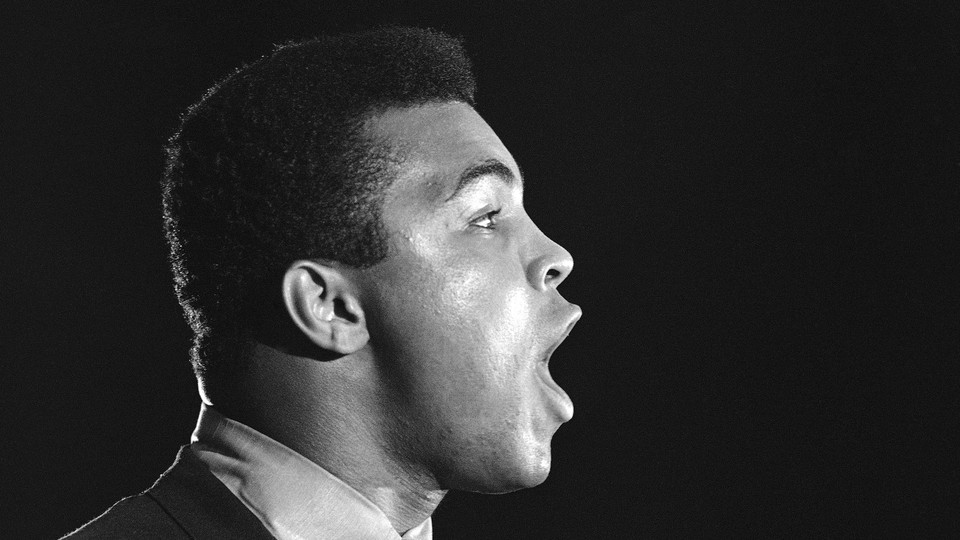

Muhammad Ali and Vietnam

His refusal to be drafted to fight in the war transcended the boxing ring, which he had dominated, at great personal cost.

Muhammad Ali’s stand against the Vietnam War transcended not only the ring, which he had dominated as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, but also the realms of faith and politics.

“His biggest win came not in the ring but in our courts in his fight for his beliefs,” Eric Holder, the former U.S. attorney general, said Saturday.

On March 9, 1966, at the height of the war, Ali’s draft status was revised to make him eligible to fight in Vietnam, leading him to say that as a black Muslim he was a conscientious objector, and would not enter the U.S. military.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he said at the time. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

A little more than a year later, on April 28, 1967, Ali, then 25 years old, appeared in Houston for his scheduled induction into the U.S. military. He repeatedly refused to step forward when his name was called—despite being warned by an officer that he was committing a felony offense that was punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. His refusal led to Ali’s arrest and eventual conviction—though he stayed out of prison while his case was appealed. His license to box was suspended in New York the same day, and his title stripped; other boxing commissions followed. Ali was unable to obtain a boxing license in the U.S. for the next three years.

The remarks and actions were even more controversial than the former Cassius Clay’s conversion to Islam in 1964. The Vietnam War was popular at the time in the U.S., and the sight of a man, especially a black man, who not only refused to serve—but did so eloquently—incensed the sporting, media, and political establishments. Ali instantly became a national pariah—perhaps the most hated man in the country, as can be evinced in this monologue from David Susskind, the American television host, who was addressing Ali: (The link itself is worth following for Susskind’s obvious antipathy toward the man on the television screen.)

I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man. He’s a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughingly describes as his profession. He is a convicted felon in the United States. He has been found guilty. He is out on bail. He will inevitably go to prison, as well he should. He is a simplistic fool and a pawn.

Nor was Susskind the only man, nor whites alone in opposing Ali’s actions: Jackie Robinson, the first black man to play in the major leagues, said Ali’s stand was hurting African Americans who were, unlike him, fighting in Vietnam.

“He’s hurting, I think, the morale of a lot of young Negro soldiers over in Vietnam,” Robinson said. “And the tragedy to me is, Cassius has made millions of dollars off of the American public, and now he’s not willing to show his appreciation to a country that’s giving him, in my view, a fantastic opportunity.”

Ali, though, didn’t see it that way: “I would like to say to those of the press and those of the people who think that I lost so much by not taking this step, I would like to say that I did not lose a thing up until this very moment, I haven’t lost one thing,” he said. “I have gained a lot. Number one, I have gained a peace of mind. I have gained a peace of heart.”

Still, Ali’s continued refusal to go to Vietnam—despite repeated pressure—coincided with the war’s growing unpopularity in the U.S. And in the three years he didn’t fight, Ali became a prominent speaker at college campuses across the U.S., as the anti-war movement grew in strength, silencing those who told him to participate with his compelling arguments:

Eventually, state boxing commissions did grant Ali licenses to fight. And when he returned to the ring, on October 26, 1970, he knocked out Jerry Quarry in the third round. The road to legal exoneration took longer. My colleague Matt Ford explains what happened:

When Ali appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court for the final time in 1971, liberal stalwart Justice William Brennan convinced his colleagues to hear the case. Justice Thurgood Marshall recused himself because he had been solicitor general when Ali was prosecuted. That left eight justices, who on a first vote sided with the Justice Department in a 5-3 decision.

Ali claimed he qualified for conscientious-objector status because he opposed the war as a black Muslim. The Justice Department challenged that status, citing his statements that he would fight the Vietcong in a “holy war” if they fought Muslims. The justices began drafting their opinions when one of Justice John Marshall Harlan II’s clerks convinced him to take home Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Blackman in America. Harlan returned to the Court the next day and, convinced of Ali’s sincerity after reading the text, switched sides.

Harlan’s move raised the prospect of a 4-4 split, which would preserve Ali’s conviction and send him to jail without explaining why. The justices instead chose to resolve it on narrow technical grounds and unanimously vacated the conviction.

Ali triumphed, but his victory came at great personal cost. As Angelo Dundee, his trainer, said Ali’s beliefs cost him “the best years of his life.” Before he was prevented from fighting, “it seemed impossible to hit him,” he said. The man who returned to the ring “was more flat-footed.”

“Nevertheless, he was so great that he still was the best among all of his opponents, which is something that must be taken into account when talking about Ali,” Dundee said. “He was robbed of his best years, his prime years.”

Ali once proudly declared: “I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me—black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.”

President Obama, in his remarks Saturday on Ali’s death, echoed those sentiments and spoke of the personal cost of the champion’s stance during the Vietnam era.

“It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled, and nearly send him to jail,” Obama said. “But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.”