The fascinating reason why clowns paint their faces on eggs

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldProfessional clowns must choose a unique facial makeup design – and they have an unusual way of ‘protecting’ it from copycats. Legal researchers Dave Fagundes and Aaron Perzanowski investigate.

Inside a church in east London, a clown called Mattie Faint is clutching a very special kind of egg. Daubed onto its surface is a studiously rendered, if somewhat rudimentary, portrait of a clown’s face. It’s one of many ceramic eggs that Faint keeps safe – they are vitally important to their owners.

Faint is the curator of the Clowns’ Gallery, a museum based at Trinity Church in London’s East End, that is popularly known as the “Clowns’ Church”. A stained glass window memorialises Joseph Grimaldi, not a saint but the patron of British clowning. The remains of at least one clown have been scattered in the courtyard. Several rooms at the rear of the church hold a rich array of artefacts, including costumes, props and other circus ephemera.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of Faint’s collection, though, are the eggs. Each one is different, and represents the unique face design of its subject. Eggs like these are kept in only a handful of collections around the world, representing a kind of informal copyright – and much more.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldThis egg-based system of registering clowns’ makeup designs operates outside the courts and is not enforced by lawyers, which makes the practice particularly interesting to legal scholars like us. We’re interested in how artists think about originality, borrowing, and copying. Our prior research has looked at similar forms of emergent property norms: the distinctive pseudonyms of roller derby athletes, and the unwritten rules of copying, inspiration, and ownership in the tattoo industry. Other researchers have investigated the intellectual property in the worlds of stand-up comedy, graffiti, drag performance, and French cuisine, among others.

So, why do clowns value unique makeup designs? How does their egg-based system work? And of all the possible options, why did clowns choose this idiosyncratic method of memorialising their identities?

Legal tools

Though fascinating in its own right, the study of informal intellectual property is more than a matter of idle curiosity. The legal regulation of creativity plays an increasingly important role in our daily lives. At the core of copyright, patent, and related bodies of law is a belief in incentives. By giving creators legal tools to control how their works are used, the hope is that they will be encouraged to produce more art, safe in the knowledge that they can profit from it.

But people who create do so in response to a host of incentives, only a small fraction of which copyright and related laws address directly. Some create out of love of their art, or to express themselves. While others seek the respect and acceptance of other creators. Formal legal incentives fail to account for these other powerful motivations.

So when a group of artists such as clowns decide to bypass legal tools by opting for self-regulation instead, it suggests that formal intellectual property systems do not address the needs of all creative communities in memorialising and protecting their work.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldThat’s how we ended up at Trinity Church to meet Faint and see the collection of eggs held there.

Faint enthusiastically welcomes us with a cup of tea and a detailed tour of the art, photos, costumes and other memorabilia that populate the museum. Faint is a member of the professional club Clowns International, and has been a clown for 46 years. He’s even met the Queen – twice – through his work.

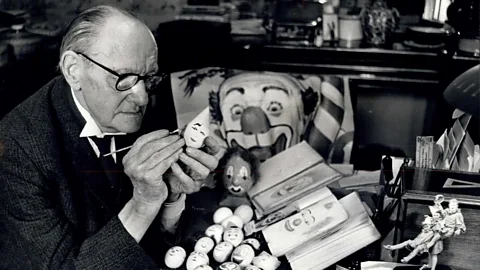

In a three-hour conversation, Faint treats us to a crash course in the essentials of clowning and the history of clown eggs. The earliest egg registry dates to 1946, when Stan Bult – a chemist by trade, though not a clown himself – began painting the faces of prominent circus clowns on eggs as a hobby. Eventually, the practice grew into what one contemporary publication called “a file of faces so that clowns can avoid copying one another”.

Bult painted eggs paying homage to prominent clowns until his death in 1966. At that time, Bult had created about 200 eggs, though Faint tells us that Clowns International only has about 40 of those original eggs in its collection. The fate of the rest is unclear. The most popular theory is that they were lent out to a private collection in the mid-1960s and mostly discarded or destroyed.

In 1987, though, Faint and other leaders of Clowns International revived the practice of egg painting. Since then, three different artists – Janet Webb, Kate Stone, and Debbie Smith – have painted eggs to memorialise members of Clowns International. The bulk of that collection, which now includes more than 200 eggs, is on display at a British tourist attraction called Wookey Hole in Somerset, which also features charmingly garish caves, mini-golf, a model village and other family entertainment. But more eggs and replicas are housed at Trinity Church.

But Faint says he did not revive and continue the egg tradition due to a pressing need to establish extralegal property rights. While there’s consensus among clowns about the importance of not copying one another, Faint does not regard a formal property system as necessary to enforce this norm. Clowns themselves do much of this work within their own community. For instance, Faint himself often provides feedback on makeup designs of early-career clowns, including steering them away from looks that are too similar to pre-existing performers.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldFaint also told us that copying another clown’s look is less of a problem than one might think. Clowns prefer to have unique looks to distinguish themselves, and even if one did try to copy another’s makeup, the differences in facial structure would likely still render the two clowns reasonably distinct.

He instead prefers to cast the registry as a way of memorialising the Clowns International membership, as conferring prestige and a sense of gravity upon those who take the art of clowning seriously. It may not mean “I can sue you”, he explained, but still represents a “recording for posterity”.

Painter skill

Our next stop was Folkestone, a seaside town near the white cliffs of Dover, where Debbie Smith paints the clown eggs that end up in the Wookey Hole collection. Smith became the egg artist for Clowns International in 2010, when she won a competition for the position.

While being the Clowns International egg artist is an honour, it will never make her wealthy. Though each egg takes her several days of painstaking work to complete, she is paid a mere £15 ($20) for each one.

Clowns International

Clowns InternationalThe results, though, are spectacular. Smith not only reflects each clown’s makeup in minute detail on a ceramic egg, she also includes simulacra of their costumes – collars, bow ties, and even hats that she recreates in miniature from material submitted by each applicant.

And not every applicant for a clown egg is successful, Smith reminds us. Clowns International screens for those who seek to use a name already used by a member or associated with a famous clown. And membership is limited to working clowns with developed visual identities. Neophyte clowns, young children, and non-performers do not make the cut.

Like Faint, Smith sees the registry more in historical than legal terms. Being in the registry means being part of the long tradition of clowns. It allows those who appear there to be seen and remembered for posterity. Smith reminds us also that whatever its serious purposes, the clown egg registry is meant to be fun, too. Many Clown International applicants ask her to make an extra egg for themselves in addition to the one destined for Wookey Hole.

The next day takes us to rainy Bournemouth, where we spend an afternoon with Chris Stone. Stone proudly self-identifies as a “suit”, not a performing clown. Like Stan Bult, Stone sought escape from his dreary day job by getting involved with Clowns International. In the late 1980s, Chris – along with Faint and others – helped to revive the practice of creating clown eggs.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldFor Stone, though, the practice is more than just a diversion. He was inspired to make the clown eggs not just something for clowns and the public to enjoy, but a formalised register to systematise the membership of Clowns International, consistent with Bult’s early vision. Stone – who for years worked as a law clerk in the Royal Courts of London – says he modeled the clown egg registry on the centuries-old practice of claiming the right to publish a book by recording its title in a register maintained by the Stationers’ Company.

Stone thus seeks to dismiss the common misconception that the eggs themselves comprise the registry. The registry, he shows us, is a written record – complete with real name, clown name, date of membership, and serial number – of all Clowns International members dating to the late 1980s. Stone kept the registry for several decades, and did intend it to have “copyright aspects”.

The written registry includes dates so that members could resolve conflicts over similar makeup designs, though such conflicts are relatively rare. And while Stone too echoes the consensus that there is an unwritten rule that clowns not copy one another, he like Faint reports that clowns themselves handle most of these concerns internally. Outright copying can get you a “black eye” in the clown community, both metaphorically (shunned by venues or fellow performers) and literally (because in rare cases, conflict resolution “comes down to violence”).

True to his status as the “suit” in a group comprised mostly of clowns, Stone also notes that the egg register confers a sense of professionalism on a group of performers who are often looked on as riff-raff. The eggs are the public face of the registration process, and Stone aspires in part for them to lend dignity and order on a joyously unruly group. This too is why Clowns International organises a clown church service. As Stone puts it, the idea of the registry and his organisation was to bring clowns up in the world, and as a former accountant and law clerk, he was the one who sought to “keep the padlock on”.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldJust before we leave, Stone asks us whether we know what’s in a large black case that’s been sitting portentously to one side on a table throughout our conversation. We don’t, of course. He opens it to reveal 40 or so of the original Stan Bult-painted clown eggs.

He arranges the 70-year-old chicken eggs on the dining table. We see renowned circus performers of the early 20th Century – people like Sir Robert Fossett, Paul Fratellini, Len “Spider” Austin, and Lulu Craston.

Stone acquired them – not cheaply – from a private collector last year, long after most clowns had written them off as lost or destroyed. As he carefully unwraps the eggs, fragile with age but remarkably preserved, he explains that we are now among a privileged handful of people who have viewed these artifacts over the last half-century. Although he has no current plans to display them publicly, they remain an important part of the larger clown egg registry project.

Inside the circus

Our final day of the research trip brings us to Hanham Common on the outskirts of Bristol, where we spend some time wandering in the rain around a seemingly deserted circus big top. Suddenly, a stocky man strides out of the tent with such purpose that it looks as though he’s about to tell us trespassers to get off the property.

But it’s not a security guard: it’s Bippo – given name, Gareth Ellis – one of Britain’s most renowned circus clowns, sans makeup. He invites us into the empty big top for an hour’s conversation. Bippo has been clowning since he was just a boy, and convinced his parents to hit the road and travel with a circus.

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldBippo is well acquainted with the clown egg register – he has had two eggs painted. The first was done when he was much younger and employed a louder visual persona, and the second more recently when he switched circuses and adopted a less elaborate aesthetic.

He regards the egg registry as serving a number of functions: it shows the new talent coming into the field; it gives guidelines of what to do (and not to do) with makeup; it helps avoid repetition of a clown’s makeup designs; and it provides a visual historical record of significant clowns. Bippo even mentions that he thinks of the register as a form of copyright, though not a legal one.

In the past, Bippo has toyed with trying to legally copyright his clown persona, but tells us he never had the time or considered it worth the trouble. Bippo has had his share of imitators though. One of his friends wanted to be a clown, and Bippo helped him along that path until the friend started to perform with a look so similar to Bippo’s that people were confusing the two. Bippo pressured his friend to change his look, and the friend agreed, perhaps wisely. While an affable and family-friendly entertainer, Bippo cuts a rather imposing figure.

(Credit: Javier Hirschfeld

(Credit: Javier HirschfeldOn our way back from Bristol, we finally visit Wookey Hole itself, after a baffling series of twists and turns down ancient rural roads. The register is one of dozens of attractions at the amusement park, housed in a room devoted to the history and art of clowning.

It sits in two large showcases, and comprises over 250 eggs, including both the modern ones commissioned by Clowns International and some of the surviving Bult eggs that started the tradition.

After driving all over the south of England to meet the people who began and continue this strange and distinctive tradition, it’s hard to know just what to say as we look at the eggs themselves. While our interest in clown eggs began as a legal research project, we’ve also learnt about a community and culture that remains largely unknown to the world outside clowning. In the end, we just stand there alongside the families who stop and gawk with us, caught somewhere between fascination and delight.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.