If time makes fools of us all, you couldn’t blame André-François Raffray for taking it more personally than most. In 1965, Raffray, a lawyer in the southern French city of Arles, thought he had hit on the real-estate version of a sure thing. The 47-year-old had signed a contract to buy an apartment from one of his clients “en viager”: a form of property sale by which the buyer makes a monthly payment until the seller’s death, when the property becomes theirs. His client, Jeanne Calment, was 90 and sprightly for her age; she liked to surprise people by leaping from her chair at the hairdresser. But still, it couldn’t be long: Raffray just had to shell out 2,500 francs a month and wait it out.

He never got to live there. Raffray died in 1995, aged 77, by which time Calment was 120 and one of the most famous women in France. She hadn’t lived in the rooms she owned above the Maison Calment, the drapery shop once run by her husband in the heart of Arles, for a decade. Instead, as each birthday thrust her further into the realm of the improbable, Calment held court at La Maison du Lac, the retirement home next to the city hospital. She had no immediate family – her husband, daughter and grandson were long dead – but journalists and local notables would regularly visit for an audience. “I waited 110 years to be famous. I mean to make the most of it,” she was reported to have said. One party piece was recounting how, as a teenager, she had met Vincent van Gogh; he was ugly and dishevelled, she said, and locals called him “the dingo”.

The pensioner appeared blessed with the stamina of Methuselah. Still cycling at 100, she only gave up smoking at 117; her doctors concluded that she had a mental capacity equivalent to most octogenarians. Enough, at any rate, to coin the odd zinger: “I wait for death… and journalists,” she once told a reporter. Aged 121, she recorded a rap CD, Mistress of Time. But even this “Michael Jordan of ageing”, as one geriatrician put it, had only so much road to run. By 1996, she was in steep decline. Using a wheelchair, largely blind and deaf, she finally succumbed on 4 August 1997. At 122, hers was the oldest validated human lifespan in history.

Some, though, believe it’s not just time that makes fools of us all. Last year, a Russian mathematician called Nikolay Zak made an astonishing claim: that it was not Jeanne Calment who died in 1997, but her daughter, Yvonne. Sceptical about the degree to which Calment had surpassed previous record-holders (the nearest verified claim at the time was 117), Zak had dug into her biography and uncovered a host of inconsistencies. First published on Researchgate, a scientific social networking site, then picked up by bloggers and the Associated Press news agency, Zak’s paper claimed that Jeanne Calment had actually died in 1934; according to official records, this was when Yvonne had lost her life, aged 36, to pleurisy. At this point, Zak alleged, her daughter had assumed her identity – they looked similar – and she kept up the pretence for more than 60 years.

When the paper went viral, the French press exploded. How dare someone slur a national treasure, the woman dubbed “la doyenne de l’humanité”? And who was this upstart Russian anyway? Zak wasn’t even a gerontologist, a specialist in ageing, but a 36-year-old mathematics graduate who worked as a glassblower at Moscow State University and hadn’t published a paper in 10 years.

Zak doubled down in response. He published an expanded paper in the US-based journal Rejuvenation Research, in January this year. It compiled a dossier of 17 pieces of biographical evidence supporting the “switch” theory, including inexplicable physical differences between the young and old Jeanne (a change in eye colour from “dark” to green) and discrepancies in the verbal testimonies she gave while in the retirement home: she claimed to have met Van Gogh in her father’s shop, when Jeanne’s father had been a shipbuilder. He also claimed there had been no public celebration of Jeanne’s 100th birthday, a key reference point in old-age validations.

As Zak admitted, there was no smoking gun; but together these pieces of circumstantial evidence did emit a fair amount of smoke. Crucially, he suggested a plausible motive: that Yvonne had taken her mother’s place in order to avoid punitive inheritance taxes, which during the interwar period ran as high as 35%.

The debate spread through the French press and international gerontological circles, becoming increasingly heated. Many dismissed Zak’s switch theory as Russian-sponsored “fake news”, as the newspaper Le Parisien put it. Certainly, it seemed to be an attack on western science. As well as Calment, Zak expressed doubts about the validation of Sarah Knauss, a Pennsylvanian insurance office manager who had died in 1999, aged 119, putting her in the silver-medal position behind Calment. Was the Russian trying to sow doubt, so that his countrymen could take the lead in the gerontology field?

For the people of Arles, it was a matter of local pride. They quickly rallied behind Calment and formed a Facebook group, the Counter-Investigation into the Jeanne Calment Investigation, to dismantle Zak’s claims. Their members included Calment’s distant relatives, and others who had known her; although some said she had been haughty and waspish, they didn’t want her reputation sullied. They had easy access to the city’s archives, while Zak had never been to Arles: what could he know? He shot back, on their open counter-investigation forum: perhaps the “Arlésiens” were just blinded by their allegiances. “Note that from a distance it is obvious that the Earth is not flat,” he wrote.

Both camps were equally adamant. One, that the woman who died in the Maison du Lac was the longest-lived human being. The other, that she was a gifted and almost inconceivably determined con artist. Which was the real Madame Calment?

An age of 122 seems to defy the limits of the possible. Even two decades later, with average lifespans still rising, no one has come within touching distance of Jeanne Calment. In the supercentenarian league – 110 and above – the three-year gap between her and Knauss might as well be an aeon.

In 1825, the British actuary Benjamin Gompertz came up with a prediction model for human mortality, one which estimated that the risk of death increased exponentially with age, doubling every eight years. His “Gompertz curve” was quickly taken up by the insurance industry. In the year after a 100th birthday, the chance of death is roughly 50%. Knowing this, Calment’s record looks even more of a statistical long shot.

In Arles’s Trinquetaille cemetery, there is little to mark out the person with the world’s longest lucky streak, apart from the small book-shaped plinth engraved “La doyenne de l’humanité” on her tomb. When I visit in the last days of August, summer has checked out early; the sky is overcast, the first autumn leaves are on the ground. On the mottled, dark-grey marble of Calment’s family tomb stands a pot of fake chrysanthemums and a yellowing succulent. Curiously, Joseph Billot, Jeanne’s son-in-law and Yvonne’s husband, and her grandson Frédéric Billot are marked, but her daughter is not. Yet the cemetery guardian, in a hut a few metres away, assures me that Yvonne is buried with her mother.

In a hotel garden next to Arles’s Roman amphitheatre, I meet three members of the counter-investigation Facebook group: Colette Barbé, Cécile Pellegrini and Brigitte Jajcaj. I mention that it seems odd that Jeanne did not put her own daughter’s name on the family tomb; was it Yvonne who decided not to, trying to tell us she was still alive? “Oh, so you followed her all the way to the cemetery, then?” jokes Barbé. Don’t overthink it, the women say. The grave wasn’t renovated until the 1960s, shortly after Calment’s son-in-law and grandson died (the latter in a car crash); by then, Yvonne had been dead for 30 years, and Jeanne only had the most recent deaths engraved.

They are an incongruous trio of detectives: Pellegrini, the group administrator, is a quick, ironic speaker whose half-Vietnamese grandfather opened the city’s first Asian restaurant; Jajcaj has swept-back grey hair, a rose shoulder tattoo and a black-tasselled padlock on a chain around her neck; Barbé is a strong-minded bourgeoise, vibrantly attired and draped in jewellery. The counter-investigation has 1,500 members, drawn from all over the globe, although the core group is made up of proud locals. “[Calment] was this elegant lady, even with a cane – an emblem of Arles,” says Jajcaj. “She held herself perfectly upright at 102, which was beautiful.”

Soon after Zak’s paper was published, the group began to scour local archives for evidence that undermined his theory. Distant members of the Calment and Billot families opened up their photo albums and personal papers. In the spirit of open debate, Zak was also accepted on to the forum, where he kept up a running commentary on the new findings. He was collegiate on the surface, acknowledging that he and the counter-investigation had a shared goal: the truth. But over time they felt his attitude – demanding people chase after evidence on his behalf, unfailingly using it to back up his own theory – begin to rankle. “Sometimes I get the impression that he thinks he understands our way of life and history better than us,” says Barbé.

But digging into the past began to pay dividends. One new photograph donated by a family member showed Yvonne posing on a balcony with a parasol against a mountain backdrop. Clever sleuthing with postcards and Google Maps revealed it to be part of the Belvédère sanatorium in Leysin, Switzerland – consistent with Yvonne’s diagnosis of pleurisy, often a symptom of tuberculosis. Another document seemed to confirm the gravity of her condition: her husband, Joseph, an army colonel, was granted five years of compassionate leave in June 1928 to look after her. Unfortunately, the sanatorium closed in 1960, and its records haven’t survived.

If the switch did take place, maintaining this fiction in plain sight would have required an extraordinary and queasy level of deception. Yvonne would have had to share a house with Jeanne’s widower, Fernand, her own father, until his death in 1942; Fernand would have had to pass his daughter off as his wife. Yvonne would have had to force her son Frédéric, seven when “Jeanne” died, to stop calling her “Maman”.

Many others would need to have been complicit. If Zak knew either the people of Arles or Jeanne Calment, the group argued, he would realise how improbable this was. A conspiracy would have been difficult to maintain in a close-knit population of 20,000, and unlikely given Mme Calment’s reputation as a “dragon”, says Pellegrini. “If people had known about the fraud, they wouldn’t have protected her,” she says.

Perhaps the most important blow from the counter-investigation group – not quite a mortal one, but close – was attacking Zak’s idea of a financial motive. The Russian had claimed Yvonne was trying to escape a 35% inheritance tax, but the group’s research led them to believe it would have been more like 6-7% – a rate the family could have managed, with Fernand Calment’s considerable assets.

But Zak refused to budge. Only a DNA test, either from Trinquetaille cemetery or a sample of Calment’s blood, rumoured to be stored in a Paris research institute, would settle the matter, he argued. But the women from the counter-investigation group believe he has gone too far down the rabbit hole to consider any theory but his own. “Even if [a DNA test] proves it was Jeanne, he’ll never accept it,” says Pellegrini. “He’ll say the tests were rigged.”

There is some debate about what happens to rates of mortality in extreme old age. Some researchers believe they continue to rise with the Gompertz curve, until the risk of death in a given year is absolute – with an effective ceiling to human life somewhere between 119 and 129. Others believe there is no such ceiling, thanks to a phenomenon known as “mortality deceleration”: the plateauing of the death rate after 105. But there are doubts about this plateau, too, due to the frequent misreporting of supercentenarians (mostly due to clerical error, rather than fraud). With such a small dataset even a few errors can skew our understanding of human limits (the Gerontology Research Group, based in Los Angeles, estimates that there are about 1,000 living supercentenarians).

The validation of Jeanne Calment’s age, though, is regarded as the “gold standard” by Jean-Marie Robine, the man who helped carry it out. I meet him at his home in the village of Pignan, just west of Montpellier. Long legs stretched out in aquamarine board shorts under his kitchen table, the researcher still has matinee-idol looks at 68. His work with Calment, carried out as a demographer for the French state organisation Inserm (L’Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), “never had validating her age as a mandate,” he explains. “It was to validate the quality of the administrative documents that attested to her age. And from what we had at our disposal, there was nothing dubious.” He points at the unbroken chain of 30 censuses – every five years up until 1946, then every seven to eight – that chronicle Jeanne Calment’s life in Arles.

Only one – the 1931 census – was puzzling. Yvonne is not listed as resident in the family’s Arles apartment, which Zak takes to mean that she was already living semi-secluded in the family’s country house, 10 miles away in the village of Paradou. He argues that she would masquerade as her mother, in order that Jeanne, the one who was really suffering from tuberculosis, could avoid the disease’s social stigma. Robine has a simpler explanation: that Yvonne was at the sanatorium at Leysin.

He is scathing about the Russian theory, flatly dismissing it as “pseudo-science”. But he and his co-validator, Michel Allard, have been criticised by Zak, and by some on the counter-investigation forum, for not being more thorough in their own corroborations. They did, however, conduct a series of nearly 40 interviews with Calment at the Maison du Lac, asking for details of her life that only she would know. She made some slips, unsurprisingly for her age, often mixing up her father and husband. (Zak jumped on such mistakes in excerpts of the transcripts later published in a book.) But many other details, such as the names of maids and teachers, largely tallied with the information recorded in censuses and school registers.

Robine is softly spoken, but it is hard to get a word in edgeways as he builds his argument. I mention the idea that a DNA test on Calment’s blood could settle the debate. Jeanne’s husband Fernand was her distant cousin, so Yvonne had more ancestors common to both sides of her family than her mother – something that would be visible in her DNA. Robine can barely hold back his indignation at the suggestion of DNA testing. “What are we going to do – just hand it over to the Russians? To an international committee? To do what? These people are caught up in magical thinking – that the secret of longevity is in her genes.”

By August 2019, l’affaire Calment had settled into a stalemate. When I speak to Zak over Skype at his dacha on the Ukrainian border, he seems more determined than ever: “With so much opposition, I want to prove that I am right,” he says. There is a flash of intellectual pride behind his poker-face. Boyish in a blue polo shirt with tousled hair, a slight smile occasionally breaks his composure. “Some people don’t care about facts. So they just hate those who disagree with them,” he shrugs.

Gerontology had originally been a hobby for Zak. He was interested in the ageing process of the naked mole-rat, an animal with an improbably long lifespan of about 30 years. But he became caught up in the Calment case after making contact on Facebook with Valery Novoselov, head of gerontology at the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP), who had longstanding suspicions about her. Novoselov’s case had been based largely on photographic analysis; he encouraged Zak, who spoke some French, to delve into other aspects, such as biographical and archival evidence. Zak says he had no intention of publishing anything – until he contacted Jean-Marie Robine about the “problems” he had found. “He always had some excuse about why he couldn’t reply, which I thought was strange,” says Zak. “It was this that made me carry on.” (Robine disputes that he was evasive, saying he corresponded extensively with Zak in October 2018.)

Meanwhile, others were beginning to have doubts about Zak and Novoselov. Robert Young, who validates supercentenarians for Guinness World Records, believes the attack on Jeanne Calment is a deliberate attempt to sow doubt about western scientific methods, amounting to “academic fraud”. He points to what he sees as Zak’s obstinate refusal to consider any scenario other than the switch theory. “Part of the scientific testing method is that we need to be open to multiple possibilities, including that one’s own position may be wrong,” Young says. “Yet he self-declares his position to be 99.9% certain.” Zak counters that he has fully analysed the opposite scenario – that Jeanne was Jeanne – in follow-up work this year, and rejects accusations of fraud.

As well as the lack of academic rigour in the original paper, Young believes its disproportionately high number of reads (70,000, when the revised version only got 1,400) might have been inflated by bots, or human intervention. Zak also manipulated a photograph of a young Yvonne Calment to emphasise what he believed (others dispute it is visible at all) to be a growth on her nose later possessed by her mother. Young alleges that such sleights of hand indicate that Zak, or people working with him, had an ulterior agenda.

Still, the switch camp had arguments that couldn’t easily be dismissed. There was Calment’s odd request, when Arles’s archives asked for them, that her personal papers be burned; and a 2006 account in a French industry newspaper of a dinner at which a guest intimated that Calment’s insurers had known of the identity switch, but no action had been taken because she was already too famous. In mid-September, Inserm released an official rebuttal paper, co-authored by Robine, Allard and two others. While it didn’t address every aspect of the Russian case, it was a cool riposte, summarising many of the counter-investigation’s discoveries, and calling for the formal retraction of Zak’s paper.

Zak upped the ante. In an open letter sent to prominent gerontologists, longevity researchers and journalists – with Vladimir Putin, Emmanuel Macron, Boris Johnson and the White House CCed – he called again for the testing of Calment’s DNA. “I don’t think such a study would be harmful to anybody,” he argued, “while the potential benefits for science are huge.” Many people thought Zak had gone too far. One member of the board of Rejuvenation Research, which had published his revised paper, resigned, saying it had “disgraced the field of gerontology in both Russia and internationally”.

Back in Arles, the counter-investigation group were also wondering about the peculiar behaviour of their “Russian friend”. He had been helpful at first, but in the depths of long comment threads he could often be provocative, even goading. One member succeeded in getting Zak temporarily blocked from the forum on 5 March for a slanging match that culminated in the Russian calling him a “crook”. “It’s very unpredictable,” says Cécile Pellegrini. “Sometimes he has a sense of humour, other times he’s odious, and we’re forced to block him for a few days.” They speculate that more than one person might be using his account, and that Zak or the Zaks might be paid trolls. (Zak denies receiving any payment or support from others.) But if Zak is a frontman, who might he be fronting for?

The theory that the Calment attack has been politically directed is dismissed by Novoselov, the gerontologist who tasked Zak with investigating her. “Look, no one in Russia cares at all about this story,” he says. “They couldn’t care less. There have been two articles in the media, and that’s it.” Novoselov says he is simply following his scientific instincts, and compares the French attachment to Calment to the national cult of Joan of Arc. “Their ability to believe in such fairytales is one of the fundamental reasons behind the creation of this [longevity] record.”

The straight-talking 57-year-old is speaking in the canteen at the Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology in Moscow, where he has just given a lecture on Calment. Having previously argued that Lenin died of syphilis rather than a stroke, Novoselov is used to courting controversy. In January, he declared that his goal was to get Calment struck off the supercentenarians register. Wasn’t it cavalier to do so before there was conclusive evidence? “What’s conclusive evidence if there is no material from the patient?” he counters. “If they showed us her medical records, then maybe we would be convinced.”

Novoselov wrote to Young about Calment in October 2018, “asking him to look attentively at the issues we raised”. The American took it, says Novoselov, as “a display of aggression by Russia against everything civilised”; after a cordial initial response by email, Young later characterised his work as a conspiracy directed from on high by “someone important”. But it’s not surprising that Novoselov’s abrasive tactics have raised eyebrows; he has threatened Young, as well as Calment’s validators, with investigation by Sledkom, the Russian FBI.

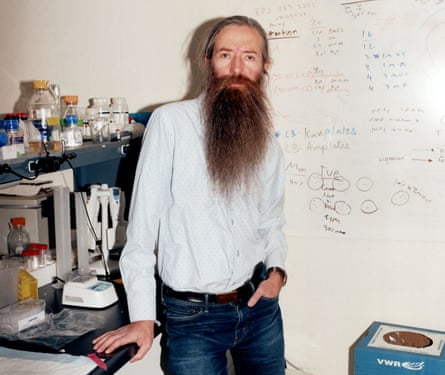

The evidence for a Russian disinformation campaign is thin, but Zak’s paper did have a second sponsor. The peer-reviewed version was published in Rejuvenation Research, the journal devoted to life-extension research edited by Aubrey de Grey, the controversial gerontologist and life-extension advocate who has claimed that, by 2100, the human lifespan could reach 5,000 years. Even if Zak doesn’t believe it, the possibility that Calment did reach 122 is tantalising for De Grey. “Anyone who is the world record holder of longevity is of interest to those of us studying the biology of ageing,” he tells me.

Speaking on the phone from London, where he is on a stopover between Berlin and his home in California, De Grey is evasive about whether his strategy is to force the release of Calment’s blood sample. But he does think it should be made available for science: “In the interests of saving lives, finding out more about ageing to eventually postpone ageing – then that’s actually quite important.” Would he want his own research foundation, Sens, to do the DNA testing? Not necessarily, he says, “but I would certainly know the right kind of researchers to recommend”.

That analysis seems unlikely to happen any time soon. The Fondation Jean Dausset, a private genetic research centre in Paris, refuses even to confirm that it is keeping Jeanne Calment’s blood; just that it has a collection of biosamples it alone can use for research under anonymised conditions. But François Schächter, the scientist who in the 1990s founded its Chronos Project, the first genetic survey of centenarians in the world, has confirmed that her blood was taken and her DNA extracted.

Twenty years ago, the life-extension field promoted by mavericks like De Grey was outlaw science. Now, the landscape has changed: the technical means for “hacking” the human lifespan have come into being, and the sector is beginning to attract serious investment. In 2013, Google invested $1.5bn in an entire division, Calico, devoted to “solving death”. PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel has given millions of dollars to Sens.

But Sens, according to its annual reports, has been running at heavy losses. De Grey says it has been spending the $13m he put into the foundation in 2011 on research for anti-ageing therapies that will save “several million” lives. But it must start to pay its way; wouldn’t securing the DNA of the oldest woman in the world be a great publicity coup, as death-dodging tech billionaires pile into the sector? De Grey bats off this idea. “I get enough media attention as it is.”

If he could study Calment’s DNA, what might he expect to learn? De Grey points out that supercentenarians’ genetic material contains a high ratio of useful information, “because they have to get more things right in order to get to the age they do”. One obvious area of interest is how Calment bypassed cancer, heart disease, diabetes and other late-life killers.

Several scientists I spoke to believe that Calment’s genome should be made available for study; but they don’t approve of the way Zak and De Grey have seemingly attempted to force the foundation’s hand. One consequence of promoting the switch theory, they point out, is that they have alienated family members whose own DNA might be crucial in understanding Calment’s.

Earlier this month, a Russian news agency announced that a woman who was purportedly 123 had died in the Astrakhan region of southern Russia. This is almost certainly impossible – even Novoselov thinks so; given her children’s ages, she would have given birth three times in her 50s. But the story underlines the need for gerontology to keep its house in order.

At the time of going to press, scientists from around the world were due to discuss the impact of the Calment affair on gerontology at a special meeting in Paris. As for her mortal remains, some think the Fondation Jean Dausset might be more open to collaboration as anti-ageing science evolves – but it is unlikely to be with De Grey. Despite telling me that Jeanne Calment does not figure high on his priorities, he plans to devote another issue of Rejuvenation Research to age validation and Calment next year.

In Arles, despite everything, the counter-investigation group are tickled by the idea that Jeanne Calment might have been a master fraudster. “I would really like the switch story to be true, like in the novels I love reading,” says Cécile Pellegrini. “I find that kind of thing super-exciting. If it’s actually true, she was really something!” But perhaps the doyenne has something else to teach the would-be immortals of Silicon Valley: what extra trouble would 5,000 years of existence bring, if we can’t get the record straight on a single ordinary lifetime?

Additional reporting by Marc Bennetts

This article was amended on 2 December 2019 to correct the spelling of Cécile Pellegrini’s surname in a photo caption; on 3 December to clarify the interactions between Novoselov and Young; and on 10 December to further clarify Novoselov and Young’s exchange and the circumstances of Nikolay Zak’s photo-editing.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion