Class calculator: Can I have no job or money and still be middle class?

- Published

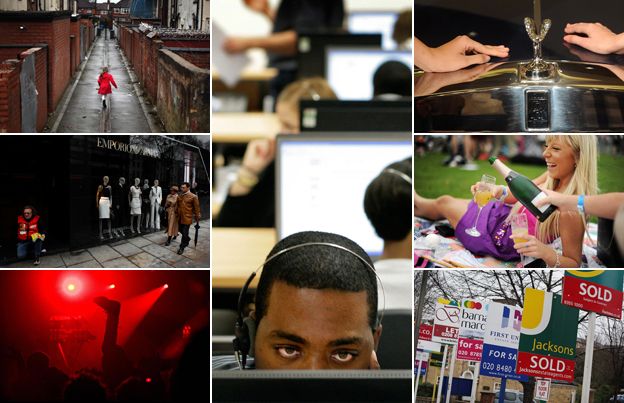

The BBC's Great British Class Survey has suggested there are seven identifiable social groupings in the UK. It's not easy to see where you fit into the class structure, writes Tom Heyden.

I'm 25. I'm a graduate. I'm a London suburbanite. Next week I'll be unemployed. And I have no savings. So what class am I?

It's often said that the British have a unique obsession with class. Popular culture is riddled with references to it. Foreign visitors struggle to comprehend the complexities of British hierarchy.

It should be an easy question - am I middle-class?

I visit museums. I go to the theatre. I watch the Danish TV drama Borgen - partly because it's good, and at least a little so I can congratulate myself for watching a show with subtitles.

I'm from a boring, comfortable London suburb. I went to university. And I love "travelling", which I understand to be oh so different from a mere holiday.

But what is class today? An attitude? An accent? Is it what you buy, or what you can buy? Your background or your present?

In the largest ever study of class in the UK, sociologists behind the Great British Class Survey (GBCS) have attempted to develop a more accurate picture of contemporary British society.

Rather than the traditional upper, middle and working-class model, they've suggested seven distinct classes.

There are familiar groups like the "Elite", "Established middle class", and "Traditional working class". But there are also new ones: the "Technical middle class", "Emergent service workers", "New affluent workers" and the "Precariat".

It's a far cry from the declaration in 1997 by John Prescott, then Labour's deputy leader, that "we're all middle-class now".

Prof Mike Savage, lead sociologist behind the survey, says: "By the 90s, there was a feeling that class labels were no longer important, we were no longer obsessed by class.

But the social and economic inequalities highlighted by the financial crisis have reinvigorated British people's obsession with class, says Prof Savage.

Despite the myriad of subtle nuances, class has historically been defined by occupation as much as anything else. A builder was working-class, a teacher middle-class and the upper class waited for their inheritance.

But a key part of the two-year survey has been exploring class in broader terms, with researchers incorporating "social capital" and "cultural capital".

The concepts were developed by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. The idea is that social networks or cultural activities - whom people know and what they do - contribute to their class and prospects at least as much as income.

"Class used to be about how much you earned, how you earned your money on a Monday to Friday. Now it's about how you spend your money at the weekend," says Harry Wallop, author of Consumed: How Shopping Fed the Class System.

I took the class survey and was deemed "established middle class" - a group that scores pretty highly in each sort of capital. In other words, I'm very lucky.

But there's a disconnection between my background and my present. And not just because I shop at Tesco and my parents shop at Waitrose.

Two years ago I moved back home. My earnings are intermittent enough that I haven't moved out yet. Certainly the very fact that I can freeload like this could be seen as definitive proof of my "established middle class" background.

But property ownership - that most traditional status symbol of the middle class - is not even a distant consideration. I've saved almost nothing since university. And I'm about to be unemployed.

The current economic situation, combined with the extraordinary boom in property prices, particularly in south-east England, means that there's a whole generation of people who are likely to be worse off than their parents.

Why should a 20-something brought up in a £1m house but now unable to afford the rent on a one-bedroom flat consider themselves middle-class?

If I were to move out tomorrow and take the test again, I'd be in one of the new classes - the emergent service workers.

Emergent service workers constitute about a fifth of the population, according to the study. They're typically young and educated, but have few savings and don't own property.

Importantly, though, they still live a very socially and culturally engaged lifestyle. They tend to live in cities or student towns. They eat out for dinner. They go to the cinema, to gigs, and they play or watch sport. It's a kind of "live for today" attitude.

"There's a different attitude towards consumption, you're consuming experience. Thirty years ago you were consuming durable things," notes Prof Richard Sennett, the author of Respect: The Formation of Character in an Age of Inequality.

Another new group is the "New affluent workers". These people are typically young, financially secure and more likely to own a house - often away from major cities, although not at the expense of high social and cultural engagement.

Few have been to university and they tend to come from working-class backgrounds, without having inherited significant economic or social capital.

In contrast there's the "technical middle class", a group distinguished by economic prosperity but also characterised by relative social isolation and cultural apathy.

"There isn't a clear hierarchy like in the past," says Prof Fiona Devine, a lead sociologist behind the class survey.

"There's a stretching out horizontally with different types of middle-class groups," adds Savage.

Then the survey identified the "Precariat" - the precarious proletariat - constituting 15% of the population. They're the most deprived class economically, as well as scoring low for social and cultural capital.

I may make very little money in the future, but the expectation is that my relatively high social and cultural capital could compensate and be turned into social advantage.

Another way in which cultural capital works is in how people assess each other, says Savage. "People with cultural capital may be making negative judgements about those who don't have it."

The pejorative use of the term "chav" is one example.

And so much about class concerns perception and self-perception.

In a 2011 survey by Britainthinks, 71% said they were middle-class - and 0% said they were upper-class.

"Even proper old school toffs reluctantly grumble, 'Well, I'm not sure, am I really upper-class?' Yes, you're a duke, of course you are," says Wallop. "It's almost impossible to label yourself without fear of being judged."

I went to a private school. It wasn't the type of school with Downton Abbey accents. Many of the private school kids talked more like the crack dealers from gritty dramas.

Private school kids typically don't want to sound like private school kids. Normally I don't offer up the fact that I went to private school.

There's no straightforward link between your actual position in society and what class you think you're in, says Savage.

"Even though I'm very comfortable materially now, my mindset is still that of somebody whose family didn't have enough money to put meat on the table," says Sennett.

It's never been easier to hide your background and move classes, argues Wallop.

"Social inequality in pure income terms is very bad at the moment, the rich have got richer and the poor have got poorer, but the great majority in the middle can move around far easier than they ever did… and move into a new class purely on the base of the shops they shop at, the holidays they go on, the food they eat.

"You can still furnish yourself with a very 'middle-class' lifestyle on not a vast budget," he says.