Israeli scientists have discovered an "invisible" ancient Hebrew transcription that was hiding in plain sight for more than 50 years. Its message? Send wine.

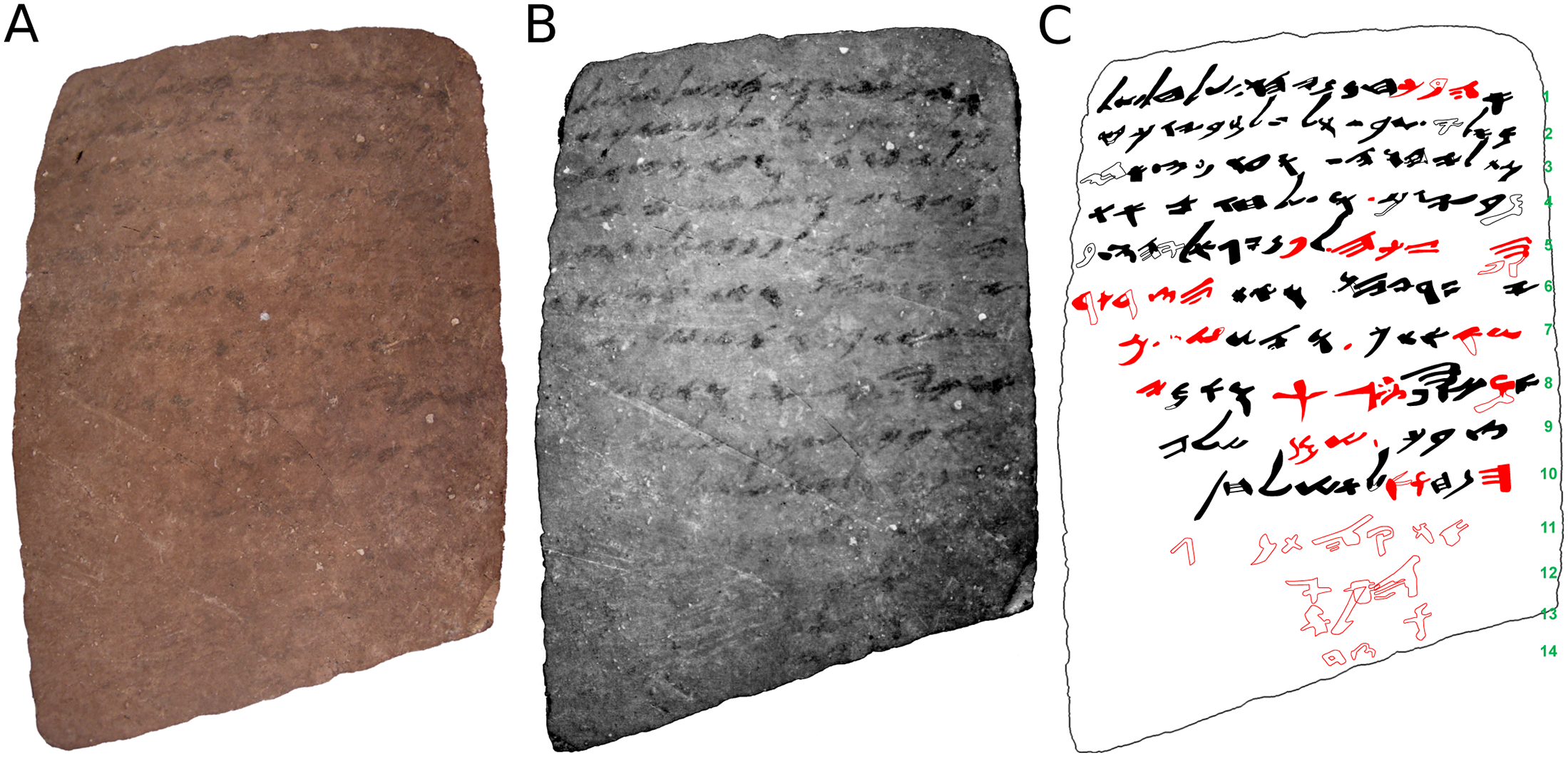

Tel Aviv University (TAU) researchers found the message on the back of a shard of pottery displayed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem for half a century. They used new imaging techniques to unlock the message that was previously invisible to the naked eye.

The ink-inscribed shard, known as an ostracon, was discovered at the Arad desert fortress in Israel in 1965, west of the Dead Sea. It dates back to 600 BCE and its message is a demand for military supplies for a force of around 20 or 30 soldiers in what was then the fortress of Tel Arad in the Kingdom of Judah.

"While its front side has been thoroughly studied, its back was considered blank," said Arie Shaus of the university's Mathematics Department and lead investigator of the study into the contents of the message.

Read more: 7,000-Year-Old Town Unearthed in Jerusalem

"Using multispectral imaging to acquire a set of images, Michael Cordonsky of TAU's School of Physics noticed several marks on the ostracon's reverse side. To our surprise, three new lines of text were revealed," Shaus said.

The first line of the message suggested that the soldiers liked to indulge in a drink, reading: "If there is any wine, send it."

Researchers were able to decipher 17 words from 50 characters, and found that the message was a continuation of what was written on the front of the shard, which talked of money transfers. The message is addressed to a man in charge of the compound, Dr. Anat Mendel-Geberovich of TAU's department of archeology explained in a university press release.

"Many of these inscriptions are addressed to Elyashiv, the quartermaster of the fortress. They deal with the logistics of the outpost, such as the supply of flour, wine and oil to subordinate units," Dr. Mendel-Geberovich said.

The revelations not only reveal the troops' demands, but shed light on "the text and the history, the economy, and the language of this period," Ronit Gadish, the scientific secretary of the Academy of the Hebrew Language told the Times of Israel.

"Every letter, every chance to decipher anything improves our understanding…. It's amazing," he added.